I walked into the gargantuan, air-conditioned sanctuary, alone but with multitudes, after having my purse cursorily inspected by a security worker. Without needing direction, I headed to the next available self-checkout kiosk.

Begrudgingly, I purchased one adult ticket for thirty dollars (plus tax), and I began to brood over whether or not my investment was sensible.

In a past life, I could enter most NYC museums for free or at a discounted rate—one of the many perks of being a public school teacher “in the city.” Now, I was one of the “normies,” who purchased full-priced tickets. I reminisced about the “good ol’ days,” the days where the city was my playground and when I didn’t have a reason to visit any one of the city’s many playgrounds.

And though I had been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MoMA) on numerous occasions, years ago, this time, I was visiting as a 37-year-old mother of two small children, who now lives states away, instead of one borough away. This time, I was visiting as a tourist on her fifteenth wedding anniversary trip with her husband and without their kids.

I adventured solo on this particular day because my person was working “in-person,” which apparently meant taking video calls in a near-empty office building several blocks away in lower Manhattan. His “change of scenery” was equal parts exciting and lackluster compared to his usual office environment: a poorly-insulated sunroom in our two-bedroom rental home in Asheville, North Carolina that faces the sun and is surrounded by green and is always just a few steps away from hearing our two- and four-year-old’s “latest and greatest.”

The contrast between then and now is jolting, but both the sum and its individual parts are beautiful, together and separate.

As I sauntered into that familiar place of refuge feeling like a stranger, a foreigner amongst foreigners, I decided to welcome new observations that would inevitably occur from this new body of mine, this new mind of mine, this new expanded heart of mine. I decided to let go of the guilt of spending an uncomfortable amount of money and to open myself up to the possibilities of wonder, inspiration, and joy that today’s tour de arte would surely bring.

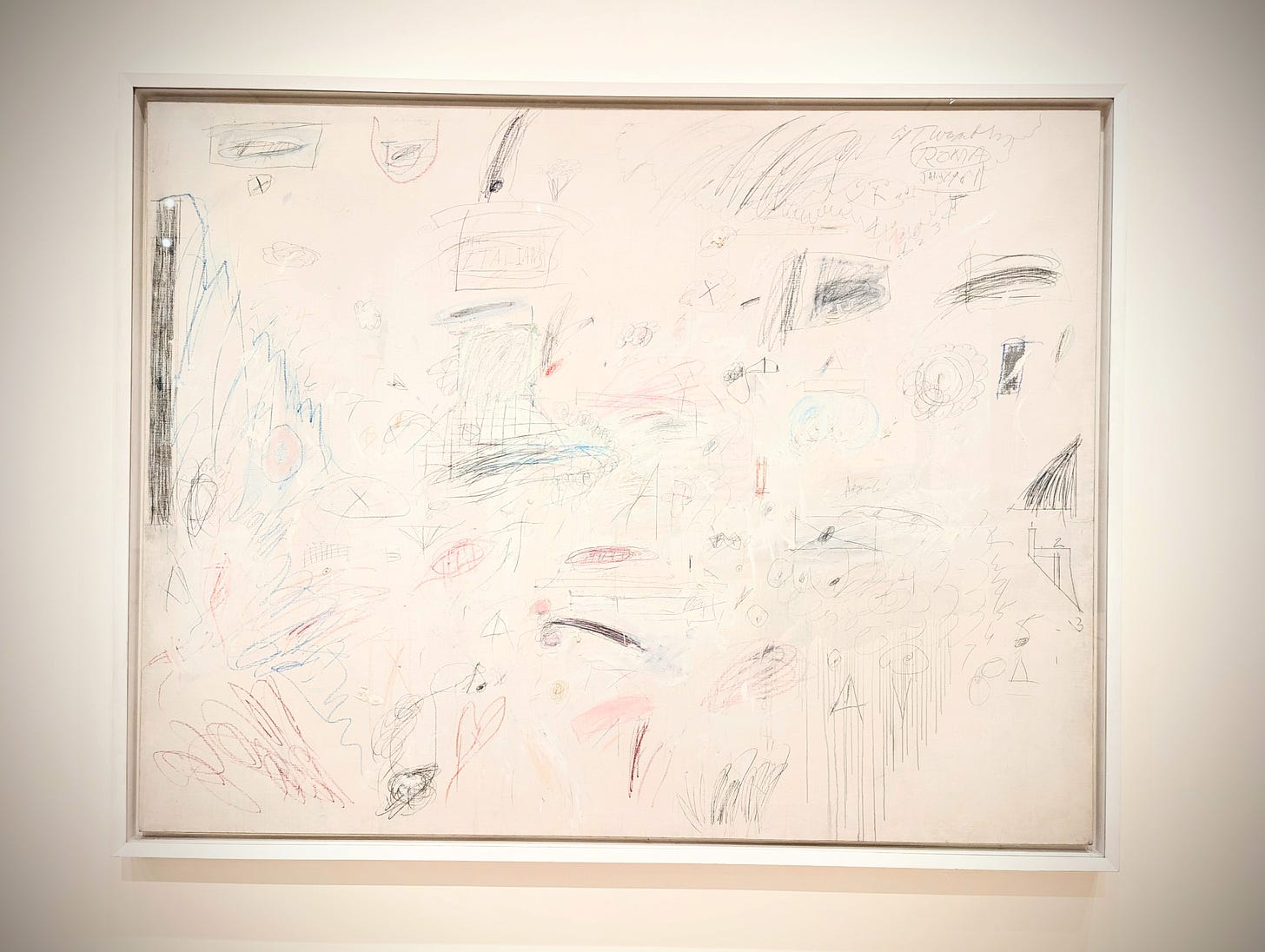

The first two floors of the MoMA consist of “metamodernism” or “post-postmodernism.” Many of the works in this genre speak directly or indirectly to a social, political, or environmental issue. It is all very confusing, interesting, and enlightening. Some of the art reminds me of my daughters’ latest collaborative art projects, and I wonder if someday one of their creations will end up on blank walls in quiet halls.

As I make my way to the upper floors, I’m greeted with familiar “faces,” the masterpieces of Dalí, Miró, Kahlo, Picasso, O’Keefe, Magritte, Manet, Gauguin, Monet, Klimt, Van Gogh, Seurat, Rousseau, Wyeth, Cezanne, Kupka, and more. I stopped for several minutes in front of each artist’s miraculous work and allowed myself to be moved. In my state of awe, I determined that my $30 ticket was indeed “worth the investment.”

To be on this pilgrimage with hundreds of others, who come from all stages, all walks, and all tongues of life, was a sacred experience. To be on this excursion of master painters and bear witness to their brilliance, in communion with one another, was a holy happening.

I felt a colossal wave of gratitude for being a human in the company of humans, gazing at the textures, the scales, the hues, the contrasts, the techniques, the influences, and the styles of other fellow humans’ interpretations of this one magnificent and grotesque life.

As I stopped to take in Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889), I began to wonder as a mother to two littles, what were the parents like of these talented beings? Did they really “see” and “know” their kid’s magic? Did they support their passions (financially and/or emotionally), or did they think their interests were undignified, worthless, or perhaps even shameful?

***

Once, when I was a pre-teen, I entered the local news station’s art contest that was being held in anticipation of the new Ripley’s Aquarium opening in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. The call asked kids of a certain age range to submit their interpretations of the theme, “Under the Sea.”

Since I was a curious, competitive, and considerably callow kid, I immediately got to work to bag the contest.

I chose colored pencils as my medium and took an empty sheet of computer paper from the printer in our “home office” (also known as the “laundry room”). I drew a lively ocean scene that included: a killer whale an orca (inspired by the film Free Willy), a dolphin (inspired by the film Flipper), a school of fish, a seahorse, a starfish, a jellyfish, various coral reefs, and patches of seaweed.

I worked on the seascape for a number of days and was very pleased with its final outcome. As I shaded in the last stretches of eggshell white with Cerulean blue, I remember taking one last survey of the final product, grinning and nodding to myself, pleased with my work and confident that I’d at least place in the competition.

Industriously, I retrieved a blank envelope, addressed it to the local news station (as I had recently learned how to do in school), deftly licked and placed a stamp in the top right hand corner, and meticulously folded and nestled my masterpiece into the envelope. I said a soft prayer, marched to our mailbox by the busy back road, deposited my entry, and turned the little red flag to the upright position with a smile on my face as wide as the sea.

I don’t recall ever showing my parents my work before hurriedly sending it off, but I do remember that historic night when my family and I were watching the news, together, in the living room, and my drawing flashed onto the screen.

My jaw dropped, and I squealed: “I won! Me! Look! Look! Look! I won the contest!”

My name, age, and hometown were typed out by the drawing, and, in that moment, I wasn’t concerned with my parents’ attention or approval. In that moment, I felt validated, sure, and proud. A stranger had “seen” and appreciated my talent, and there it was on the screen: proof that I was indeed an artist and not “just a kid who likes to draw for fun.”

After the announcement, I jumped up from the medium-pile, sand-colored carpet and turned to face my parents and digest their reactions. I remember my mom and dad’s eyes were wide in total astonishment, and I thought to myself: I did it.

I finally won.

The prize was four general admission tickets to the new attraction that housed giant tanks of all sorts of aquatic creatures: sharks, stingrays, eels, fish, jellyfish, seahorses—even alligators and penguins, according to the advertisements I had seen on TV. I pictured myself in the places of the kids in the commercials, the ones with their parents and siblings, smiling and happy and perfect.

That was going to be me; I was going to be one of those kids, I thought.

When we got the physical tickets though, my reality did not suddenly transform into that fairytale. I’d ask my mom when we were going to go, and she’d answer, “I don’t know yet. Soon, honey.” And then a week would go by, and I’d ask her again and would be met with a similar response: “I just don’t know, okay? I’ve got to figure out what we need to do and when we can go.” Then, months went by, and I’d muster the courage to give a gentle reminder, “Mom, the tickets have an expiration date.” And, she’d respond: “I know. I know. We’re going to go. I promise. I just gotta figure it all out. Now don't ask me about it again.”

The year sailed by, and then one day, while my mom was cleaning out her purse, she came across the crumpled tickets and remarked, “Oh, shoot! I forgot all about these!” And then I saw her face turn from the brightness of discovery to the darkness of guilt, as she read the expiration date at the bottom and declared: “Ah, man! We missed our chance.”

Reflexively, I ran to my room, trying to win the race against my tears. I won, albeit by a narrow margin. Tears of exasperation pelted my pillow like a torrential downpour on the vast surface of the ocean. They joined without notice, invisible, to the inhabitants of the surrounding seascape: a whole world unaware of their presence, unmindful of the depth of their hurt.

And, as I allowed my body to sink into my bed, I drowned there in the abhorred microcosm that was my home.

***

After viewing the “French Landscapes” exhibition, which included Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889), Rousseau’s The Sleeping Gypsy (1897), and Seurat’s Evening, Honfleur (1886), I made my way into a much smaller room comprised of only three works, and, to my right, on its own, there it was: Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948).

I paused (as I always do in front of this particular painting), and I cried.

I pictured myself as the young woman depicted in the foreground, facing away from the viewer, statuesque, sitting in the tall grass, looking back at a farmhouse in the distance.

The divide between her location in the field and the location of her home was palpable.

I understood what it felt like to make progress, to move forward, while also losing ground, longing for a different reality.

I understood how possibility and impossibility could co-exist.

I mopped my tears and read the information on the placard mounted by the painting:

“Set in the stark landscape of coastal Maine, Christina’s World depicts a young woman seen from behind, wearing a pink dress and lying in a grassy field. Although she appears to be in a position of repose, her torso, propped on her arms, is strangely alert; her silhouette is tense, almost frozen, giving the impression that she is fixed to the ground. She stares at a distant farmhouse and a group of outbuildings, ancient and grayed in harmony with the dry grass and overcast sky.

Wyeth’s neighbor Anna Christina Olson inspired the composition, which is one of four paintings by Wyeth in which she appears. As a young girl, Olson developed a degenerative muscle condition—possibly polio—that left her unable to walk. She refused to use a wheelchair, preferring to crawl, as depicted here, using her arms to drag her lower body along. ‘The challenge to me,’ Wyeth explained, ‘was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless.’

The high level of detail Wyeth gave to every object in his paintings encourages intense inspection, but his titles reveal the inner significance of their outwardly straightforward subjects. The title Christina’s World, courtesy of Wyeth’s wife, indicates that the painting is more a psychological landscape than a portrait, a portrayal of a state of mind rather than a place.”

You can only control what you can control, and you can’t control what you can’t.

***

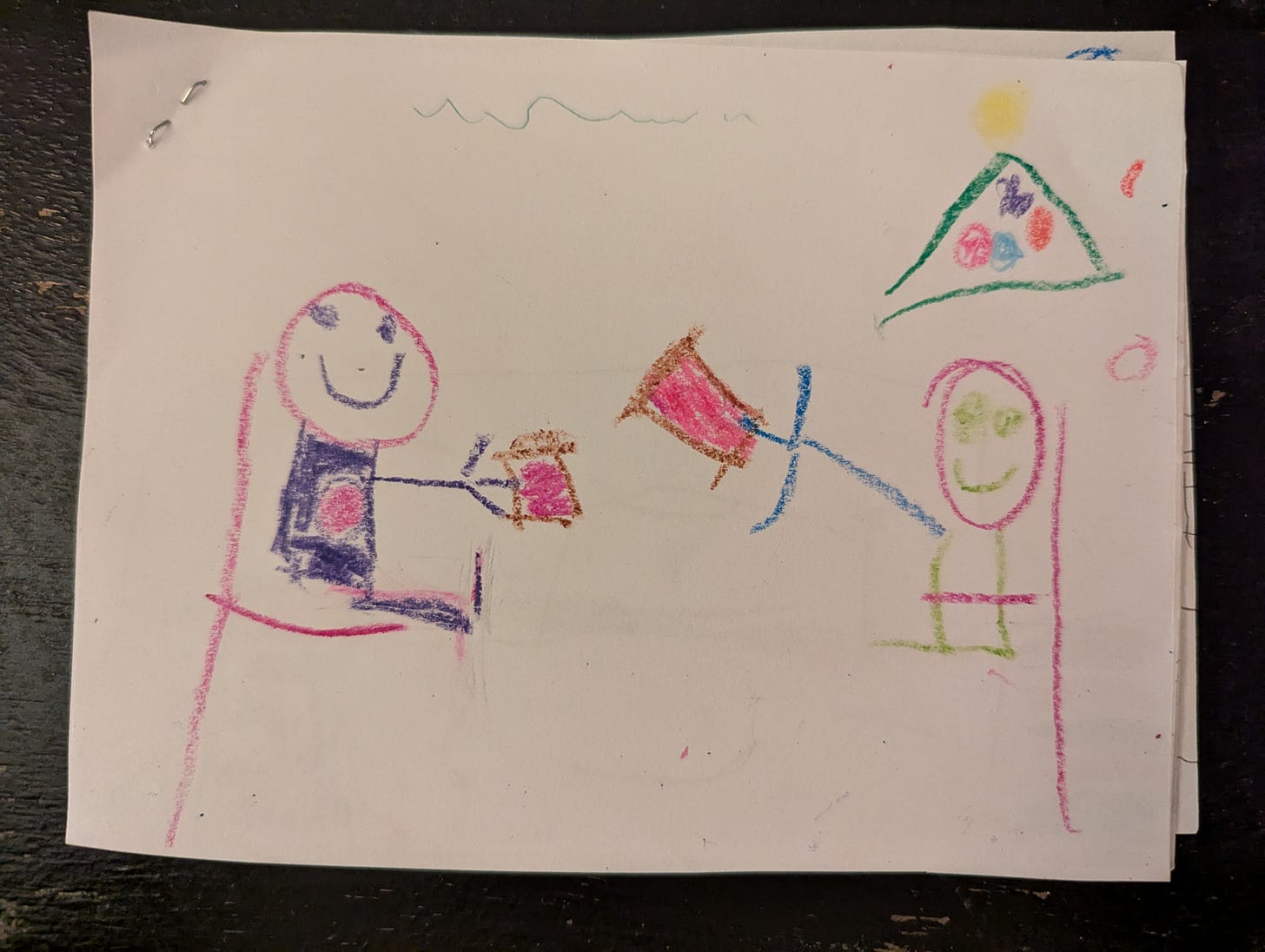

Of late, my four-year-old daughter has started to exhibit new growth in her artistry. Her drawings, paintings, and “art installations” (read: fairy houses) involve more structure, more detail, and more nuance. She’s able to explain her work with impressive vocabulary and also articulate her work’s purpose and its intended audience.

Some of her drawings are for close friends or her little sister or her Mama or her Dada, but others are just for her: her very own ~self-created~ prized possessions. She takes these self-given gifts and delicately adheres them to her bedroom walls or door, using Scotch tape, with a smile as wide as the sea, a smile I immediately recognize.

With each completed work, I tell her how proud I am of her effort and how delighted I am by her creative choices. I then ask her how she feels—how she feels inside her body—and she responds: “Proud” or “Happy” or “Good.” And, I tell her that that’s what matters the most: how her art makes her feel. I advise her to soak up that warm feeling, bottle it up for as long as she can, and to never forget it.

“It’s very important,” I say to her.

“It’s very important,” I say to myself.

If you enjoyed reading this personal essay, please like and/or leave a comment. Hearing from you really brightens my day and encourages me to keep doing this work! :)

From now until the New Year, take advantage of Human/Mother's "Celebration of Fall" Special Offer. You’ll receive a 50% discount off an annual subscription ($50 value for $25)! Your support gives me the fuel to keep this passion project going and to deliver quality personal essays straight to your inbox every month. Thank you!

💯! It's hard but necessary work. 🙏🏼 Thank you for taking the time to read my words, Alexa! 💕

This is beautiful. I love how you related your own loss to the picture possibility vs impossibility. Really lovely xx