Hi, dear Reader!

How are you? I hope you’re taking time to feel the sun, to breathe in fresh air, and to enjoy the beauty of nature. If you’re new here, I’ve linked to previously-published personal essays throughout this piece. I consider these gems to be “required Human/Mother reading,” and I do hope that you’ll bookmark and read them.

In addition, since Helene, I’ve gained quite a few new subscribers. Some of you have even pledged your belief in my writing by becoming a paid member of this community. I am so thankful for your encouragement—both paid and unpaid. Human/Mother is free and available to all and will continue to be for the foreseeable future, but, if you feel so inclined, I welcome your financial support. I am a mother to two small children and am also in the middle of a career pivot. I was a middle school English teacher for ten years before becoming a mama and am now seeking contractual work as a writer. What a dream, indeed!

If this essay ends up resonating with you, please consider hitting that heart at the end of the post, leaving a comment, and/or re-stacking. I’d love to hear from you! Thank you, and happy reading!

***

During our Helene displacement, I read P.D. Eastman’s children’s book, Are You My Mother?, to my daughters while we were staying with my in-laws. Although we had read the book several times prior, my two-year-old and four-year-old still found the whole concept of the book hilarious. I mean: a bird searching for its mother and asking various animals and machinery if they are her? That’s pretty dang funny—classic toddler humor.

The plot reminds me of the popular game I play with my daughters where I ask them if they’re a kitty-cat or a puppy-dog or a ribbity-frog or a bunny-rabbit, etc. while they imitate these animals through movement or by sound. In between their transformations, I tickle them and say, “You’re not a _____! You’re my E_____ or O_____!” They love it; I love it. It’s the best.

The resolution of Eastman’s book occurs when the excavator returns the baby bird to its nest where it’s reunited with its mother, and though it hadn’t seen her with its own eyes before, the baby bird intuitively knows that she is, in fact, his mother.

The last line reads: “You are a bird! And you are my mother!” And after reading those familiar words, I asked my daughters why they thought the baby bird knew who its real mother was, and my four-year-old enthusiastically responded, “Because of love!”

And that, dear Reader, is the truth: we know our mothers because of love.

***

Western North Carolina’s Helene “experience” is still ongoing. We are on day 47 of non-potable drinking water. As I’ve already recounted here in this publication—after Helene ravaged our sacred mountains—we spent five days in Asheville without water or power, and it was then that we decided to leave our destroyed mountain city, snuggly-nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains, in order to attain the resources that our family needed while not taking away from those who needed it most.

As I've recounted in a previous post, we were one of the lucky ones. Our home and our vehicle were not damaged. Our livelihood was not stripped away from us. And, our health was not affected. We sit in gratitude daily as we pass through the areas of our town that have been devastated, and we stand with our community as we seek ways to help others get back on their feet and find solid ground again in this time of both physical and emotional water—40 trillion gallons’ worth.

Our neighborhood in North Asheville was without power for ten days and without water for 22 days. My family and I were displaced for 17 days and for only a handful of those was I able to acquire some childcare relief.

Once power and water had been restored, we bolted back to our small home, desiring routine, comfort, and normalcy again. The time away was necessary, but it wasn’t a vacation by any means. Our children, particularly my oldest daughter, struggled greatly. Emotions ran high while patience ran low. It was a lot and still is in some ways, as our lives haven't totally returned “back to normal.”

The experience has been revelatory on so many levels, but the one thought I keep coming back to is this idea of mothering and how in our darkest hours, we need the mothers: the light carriers and the helpers.

***

Last Friday, after our first full week back in Asheville, I stopped by the Baptist church on our way home from my four-year-old’s preschool. My family needed more water, and I’d heard from a neighbor that it was a resource center that was open to the public and had plenty of filtered water available for free.

As I pulled into the parking lot, I scanned the scene: one giant water tank on a semi-truck from Mississippi was there, along with a few pallets that held several cases of bottled water and a table filled with black to-go boxes. Volunteers wearing the same shirts and baseball caps were buzzing all around, busily helping folks like me—who were still seeing stars after the absolute sucker-punch that was Helene—load Asheville’s ~hottest commodity~ into their vehicles.

It’s been nearly two months since Ashevillians have been without potable water in our homes and businesses. And though the Water Resources Department has made considerable progress in repairing the North Fork Reservoir—where 80% of Asheville (including my family) gets its water—there’s still a long road of recovery ahead.

I braked to ask a volunteer what the deal was, to which she quickly responded with a big smile on her face. Joy Personified let me know that the water tank was full of clean water and that I could bring whatever vessels from home and fill as many of them as I wanted, every day, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. She also directed me to the cases of bottled water and told me to take what I needed.

Her positive energy collided with my negative energy, and I noticed my body slipping into freeze-mode. Was I in trouble? I asked myself. “No, you’re safe,” I whispered to myself.

I asked her how long the water would be here, and she, meeting my worried eyes, said, “For as long as it needs to be.” I continued to notice what I was noticing—an increased heart rate, a held breath, an intense grip of the steering wheel—and then, with an impeccable timing that slammed me back to the reality of not just being a natural disaster survivor but also being a parent, my four-year-old loudly inquired and demanded: “WHAT’S THAT MEAT? I SMELL MY FAVORITE MEAT! I WANT IT—RIGHT NOW, MAMA!”

Sheesh! The after-school mood swings of a preschooler are not for the faint of heart. (Parents know.) I shifted in my seat to look back at her and softly said, “I hear you. It sounds like you’re hungry. Let me investigate.”

Noting the exasperated facial expression on my face, the volunteer ~got the message~ and cheerfully said, “We have free hot lunch from World Central Kitchen today: pulled pork and macaroni and cheese. How many boxes would you like?” My throat caught as tears began to form. Her softness broke me. “Three boxes?” She suggested, acknowledging my decision fatigue. I began to nod and then said, “No, no. Just two. Thank you. Thank you so much.” My words wobbled out like a woman in her final month of pregnancy: enervated and grateful.

The middle-aged woman with silky peppercorn-salt hair then bounced away and swiftly collected two boxes (along with napkins and plasticware) and handed everything over to me through the open passenger-side window. “Thanks again,” I mustered, failing to hide my clearly conspicuous feelings. I imagined the display was equal parts comical and endearing like that of a game of hide-and-seek with a two-year-old. Her tenderness was such an unexpected gift and reminded me of my mother, or, at least, parts of the mother I once knew as a small child.

***

For those of us who grew up in a household that invalidated our feelings, our automatic responses to feelings of angst and despair is: “Well, my childhood wasn’t that bad. Other people have had worse experiences than me.” But, the truth of the matter is that for many of us who grew up in homes that ignored its problems, that ruled with fear and aggression, that used the Bible as a weapon and a justification for unacceptable speech and behavior, our experiences were not okay. And though I can point to moments of tenderness that miraculously occurred in the jumble, I am still grappling with the trauma, still searching for healing, still tending to my inner child, and I’m doing it largely alone.

My atomic family’s dynamics have drastically changed in the last decade.

After my fourteen-year-old brother’s suicide and the deaths of all of my remaining grandparents, all things that were burgeoning towards falling apart eventually did—namely, my parents’ marriage and, subsequently, their individual bonds with their four surviving children.

One by one, my sisters and I began to cut off all ties with our mentally-sick father, and by the time I had my first child, I had finished the task by blocking my dad on every social media platform and messaging service. I could no longer sustain the relentless attacks and demoralizing harassment. Almost immediately, my world became less clamorous, more tranquil. Initially, my mind lied to me and screamed that I was a terrible daughter—an abhorrent human being—but, I knew deep in my heart that I had made the right choice for me and for my growing family.

My relationship with my mother has changed, too, and not in the way that I’d ever imagined: we’ve drifted apart. Years of unresolved emotions and big, elephant-in-the-room ideological differences drove us miles and miles away from each other.

Oh, and, of course, she’s not the only person to blame for this Great Divide, for this sea of turmoil and shame that I find myself floating in. I, too, am culpable, and I am sad about it. There is a part of me that regrets pushing away the people who mean the world to me—my mother and my siblings—during seasons of growth and exploration, of anxiety and depression, of life.

There is a part of me that prides herself in landing where I landed, anchored on a continent of order and function. But then there is another part of me that forlornly grieves the relationship with my mother that I do not (and likely will not) have after giving birth to my two children.

Instead of our bond strengthening and deepening, it has weakened and nearly diminished. I am here; she is there. What started as a puddle’s measure of distance is now an ocean that separates us.

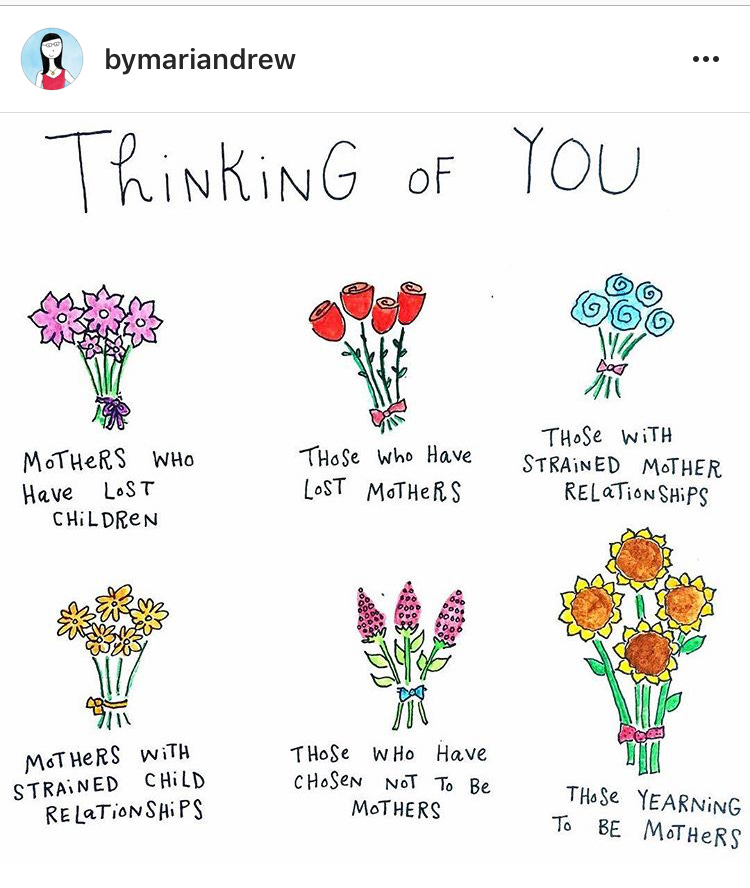

An added difficulty is that I rarely find stories about this painful position in parenting. Very few people talk about this kind of unanticipated mourning, this kind of time and energy suck, this kind of suckiness.

It’s lonely and burdensome and real and deep.

***

After waving goodbye to Joy Personified, I drove up to the next station and gathered two cases of bottled water (with the help of a sweet, seventy-something-year-old gentleman) and pulled out of the parking lot to head home. My mind, still curious about its body’s visceral reaction to the woman’s tenderness, began to wander, canceling out the obnoxious whining echoing from the back of our Toyota Sienna: Why was I so emotional? Am I about to start my period? Am I just really tired? Am I hangry? Am I just a broken human being? What’s the matter with me? Why am I crying in response to a stranger’s kindness? Why does life have to be so heavy all the f*cking time?

I quickly berated myself, telling myself to stop being so ridiculous, to quit being so dramatic, and to think logically.

And then it dawned on me: my body had been operating in trauma-response, and the generosity of a stranger was the forceable finger on the madly-spinning globe that stopped the swirling and directed: “Hey, slow down and feel for just a minute. Why don’t ya?”

At that same moment, I found myself driving past one of the most picturesque places in Asheville that had remained relatively intact after Helene: Beaver Lake. I also realized at that moment that I had been triggered not only by the woman’s maternal care but also because I had been in a church parking lot, a place that is simultaneously very familiar to me (due to my upbringing as a preacher’s kid) and also very foreign to me (due to my current detachment from the church). There’s a great deal of pain that lives in this particular space of my heart, and—my goodness—is it complex.

***

Since we’ve re-adjusted to being back at home and the boil water notice being in effect, I’ve been giving my daughters interesting baths.

Prior to our first “bath,” I laid out all the new bath-time rules:

One kid at a time

Eyes and mouths closed (as much as possible!)

Listen to Mama (because it’s her job to keep you safe and clean!)

No licking lips

No licking anything

No playing

No silly dances or wiggles or booty-shaking

No bubble baths

No toys

Pretty much, no fun!

Instead of our usual full tub of water, I run water from the faucet and use soap and a freshly-laundered washcloth to clean their bodies. To wash their hair, they sit on their bottoms, facing away from the running water, and I gently guide their scalps underneath the not-too-hot and not-too-cold flow of precious H2O, all while cradling the backs of their heads with my left hand and working the shampoo into their long, straight hair with my right. I rinse their hair like a professional hair stylist, sliding the shampoo from the tip of the forehead to the back of the cranium, directing the soapy water down their glistening, golden locks, all while reminding them to keep their mouths closed, to keep their hands out of their mouth, to keep their bodies rigid.

“Please and thank you, ma’am,” I say to them with utmost sincerity.

The simple act of washing their hair under the faucet has summoned long-forgotten memories of my own mother washing my hair as a small child.

Growing up, bath-time was our evening report of how mom’s day had gone.

My sisters and I could decipher mom’s mood by the sound of her breath and the force of her movements. Puffy, strained, and/or deep breaths meant that things had not gone well. Pulling and/or jerking of our heads were other insightful clues.

There were, however, other times when she held her breath in focused work and spoke softly to us, instructing us to turn this way or that. There were times when she would gently, gingerly, and lovingly guide our scalps under the running water—our captain masterfully docking her boats to shore, dexterously guiding her vessels back home.

I look back on all those bath-times and am reminded of the pain and suffering of my childhood but also the love and comfort. And though there is a darkness that pervades those fuzzy memories, there are also glimmers of light that mix into the fold like the “magic potion” that my daughter recently formulated at school during Halloween week. It is because of her, this woman who left a broken home and married a charismatic narcissist at 16, this woman who dropped out of high school (and cosmetology school) and chose me, birthed and cared for me at the callow age of 17, that I am able to have the life that I have now, a life that is full and rich and extraordinary.

I so badly want the relationship with my mother to be simple, but it’s simply not.

There are parts of me that ache for my mother’s comfort, and I didn’t realize how massive and influential that part of myself lived and breathed right under the surface until my emotional collapse with that volunteer at the Baptist church. I didn’t realize how much I needed to be held after Helene, after what was indeed a harrowing month of stressful unknowns with a remote-working husband and two small children.

The need to be mothered doesn’t end after the age of 18. It persists, and we must be open to receiving it as well as supplying it—unapologetically, selflessly, graciously (most of the time).

Joy Personified’s tenderness held me for just a few essential minutes, and, despite its transience, it was long enough to warm this worn mama’s heart and to be reminded of the good that exists in the world, even in the in the wake of a horrific natural disaster and in the midst of a turbulent election year. (Note: My interaction with Joy Personified occurred before the election results, but the message still applies.)

***

The topic of mothering fills my head most days: how I should mother, how I was mothered, how I hope my daughters will mother others someday. Even before Helene, I’ve ruminated on the importance and the impact of our jobs as mothers in our homes, in our society, in our world. Now that I am a mother, it has become clear to me that moms deserve more credit for keeping our Universe suspended, in order, going.

Yes, some of us, maybe many of us, have imperfect biological mothers. Yes, we have strained relationships with them for myriad reasons, non-existent relationships with them (either due to adoption, death, or estrangement), and/or complicated relationships with them (due to a wide range of debilitating mental or physical health conditions). But, one thing that is for certain—that life has taught me—is that despite the hurt in my heart, the mothers still show up when you need them most.

With this idea in mind, I propose a rewrite of P.D. Eastman’s Are You My Mother? The revised edition would center around an adult bird instead of a baby bird:

The kitten is the Trader Joe’s cashier, a self-proclaimed “cool aunt,” who distracts your tired, hungry children from the sweet treats near the counter with bright, colorful stickers. “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The hen is your MIL who always has her door open and a comfortable bed with clean sheets and a seat at the table with a nourishing meal placed in front of you and a glass of red wine. “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The dog is your best friend since high school who opens her home to your family when your home is closed and gives you a long hug and tells you that she’s happy you’re here. “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The cow is the yoga instructor, a fellow local mama of two, who holds space with her grief-stricken community and invites grounding and offers hope, resiliency, and gratitude. “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The car is the friend from college who sends her brother-in-law to our house to deliver a tank of gas to our front doorstep when we were unable to communicate with the outside world and find gas to flee Asheville. “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The boat is the unknown woman who stops to help you load your two small children and an obscene amount of groceries into your minivan (because you had to throw everything away in your refrigerator). “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The plane is all of your friends who live in New York, Ohio, Texas, Louisiana, Virginia, and Australia, who message you to make sure you and your family are safe and okay. “Are you my mother?” I ask them, and they respond, “Yes.”

The excavator is your therapist who listens to you, who lifts you up, who helps you find your safe home again and again and again. “Are you my mother?” I ask her, and she responds, “Yes.”

The mother bird is your birth mother who, on the rarest occasion, sees her 37-year-old daughter—really sees her—and tells her that she’s a good mama and that she’s so proud of her. And then I see my mother, and I say, “You are a human! And you are my mother!”

***

And, as I continue to lean over the tub once or twice a week and anxiously wash my daughters’ hair, I wonder if they, too, are picking up on how my day has gone. I wonder if they, too, are deciphering my breath and my movements. I wonder if they, too, are picking up on the fear, worry, and stress that resides in those telling spaces. I wonder if they, too, are picking up on the love.

And, then, I wonder if they will look back on fuzzy memories and offer me grace, understanding, and compassion. I wonder if they will hold onto the shimmers of light instead of the swaths of darkness. I wonder if they will remember their mother’s tenderness.

And, lastly, I wonder if they will carry the torch that their mama carried—that all mothers carry—and courageously use it to illuminate this dim world.

I hope so.

Thank you for sharing this, Katrina. It's a beautifully-written piece. I'm sorry for all that you've been through. And I hope things are doing a little better now in Asheville. 🙏

This is such a moving essay, beautifully written and meaningful on so many levels. Thank you for sharing it.

I used to read “Are You My Mother?” to my son when he was small (he’s now almost 40!), and I often felt like crying as I read it. It was the concept of losing a mother, that universal need for a mother no matter what age you are, that got to me—and still does, even at my advanced age (not saying!). It’s a need that never does go away.

Your idea of a rewriting of “Are You My Mother?” for grownups, with the animals all saying “YES!” to being our mothers, is brilliant! We desperately need mothers right now—and to mother others. Most of us have a hole in our hearts marked “Mother.” I know I do/-and mine has been gone for 25 years!

I hope your situation in Asheville improves soon. What a horrible time you’re going through! I live on the other side of the country and had no idea it was still so bad there (not much news about North Carolina here!) I’m so glad your home and cars are undamaged and that you and your children are physically safe. I’m sorry for beautiful Asheville too. We visited it once 40-plus years ago and I still remember how beautiful it was. Wishing you the best. Keep writing!❤️