I thought it was him.

Like a gazelle standing straight-necked in the Sahara, I paused for several breathless seconds, staring at the man walking towards me and my girls. My heart began to race; my blood iced. Frantically, I surveyed his features, searching for the tell-tale signs of tall-grass danger.

Similar build—though I thought too tall, but it was hard to tell from my perspective, standing at a higher elevation on a ramp of a boardwalk leading to the beach I’ve known for all my life. Eyes? Couldn’t tell because he was wearing sunglasses. Seemed grayer, but that could be true now after seven years’ time. His legs, arms, and torso were too long—I thought so, anyway. He had a similar grimace though, which made me second guess all the facts that I’d just collected.

When you’re prey in the presence of a predator, you lose all you know and rely solely on your senses.

I started to walk faster up the ramp to the long boardwalk that led to the beach, ushering my two girls—my two little suns—to “pick up the pace!” and “stay close to Mama!”, all while the hot star above beamed down on us with cruel precision.

Gasping for air (due to the humidity and my panic), my tired body exerted a marked energy, moving the loaded-down wagon with conviction. I deliberated: “We can’t turn back now because we would be discovered, for sure. If it was him, I’d be alone with my two innocent children. What would he do? I feared it wouldn’t be good. But, if we make it to the white sand before he puts together who I am—who we are—then maybe we’d have a chance of blending in with the beachgoers, maybe we’d have a chance to be safe.”

After a few more long sweeps of his body and gait, I concluded that, no, it wasn’t him. Relieved, my body released the built tension, housed in my shoulders and jaw, and slowed its heart rate with every deep and cleansing breath.

It wasn’t always this way, I thought. Though things have dramatically changed over the last ten years, over the last thirty-eight, and, before I knew it, here I was: a grown daughter scared of her own father.

I observed my daughters, skipping down the boardwalk, holding hands, giggling. Tears began to stream down my face. I marveled at their carefree state. They were not in trauma response. They were not picking up on any signs of any danger whatsoever. They were not gazelles; they were a lioness’s cubs.

It wasn’t always this way.

I imagine when I was born, he was a different person. Of course, he was.

I imagine that he held me, his newborn-firstborn, with pride and joy. Of course, he did.

I remember when he used to caress my round cheeks or rub my smooth forehead with the backs of his dewy hands. I remember that brief period of time when he used to make me and my siblings fresh doughnut holes, coated with powdered sugar, just like the “hot-now” Krispy Kreme dots that he loved. I remember when, on the weekends, he used to make us a full breakfast—his favorite meal of the day—fried eggs, corned beef hash, grits, and buttered toast. I remember him calling for us from his bed, from his dark den, pleading with us in his playful, childlike voice to lay down beside him when he was glued to the mattress, anchored by depression. I remember him asking us about our day and telling us that he loved us. I remember his tenderness.

These are the memories that make me grieve the most: the good folded into the bad, the love tucked into the pain.

How can a person be affectionate and also abusive?

How can a father have the wherewithal to hurt his own daughter?

How can a lion turn his cubs into prey?

Of course, there are many things I can point to to blame for his steep decline: his alcoholic and MIA father and stepfather, his mother’s premature death at 49 to esophageal cancer (due to secondhand smoke), his mental illnesses, his broken dreams, his failed marriage, his nebulous opioid use. I think the final blow to his mind was my brother’s suicide. When he discovered my fourteen-year-old brother dead in his closet, when he laid his young, cold body on the beige carpet, when he begged God to resurrect his one and only son—the carrier of his family name—like He did for His one and only Son, I think that was the moment when my dad lost all faculty.

I wasn’t home at the time. Erik and I were living in New York City.

I was chasing my own dreams, escaping my ‘back-home’ reality, attempting to break the cycle I was born into. And though this memory of my dad with my brother is a manufactured one, based on firsthand accounts, I still cry thinking about the scene. I still cry thinking that this was the point of no return for my dad. I still cry because I should have been there as the oldest sister, the protector of the herd. I should have been there to hold my brother’s hand as he crossed the River Styx and entered the Great Beyond.

My dad didn’t work for years towards the end of my time at home.

After he was voted out of the umpteenth church, he became a life insurance salesman, and our family lived off of renewals. To help contribute to the household income, my mother returned to work as a preschool teacher for a Methodist daycare. She ended up fracturing a bone in one of her feet while on the job and was forced to take medical leave. Enter a somber procession of pain-relieving drugs, cigarettes, and a foreshadowing silence in our once-lively home. With televisions and video game consoles in every room, there were plenty of distractions in place to escape reality and, boy, did my parents (and my siblings, for that matter) escape.

They ran away from their haunting reality: they were unable to achieve that bright and shiny American Dream. They weren’t able to be the perfect parents, despite their convincing appearances. They had made poor life choices—getting married at 16 and 18, having me at 17 and 19—and, as a result, they struggled financially for years, living paycheck to paycheck, relying on charity from churches and non-profit organizations, and surviving off of government aid.

A lion’s primary role in a pride is to protect and provide food for his cubs.

My father did not do that. He did the opposite.

So, why am I still asking ‘why’?

***

As I continued to walk down the latter half of the boardwalk, I worked on settling my nervous system by focusing on the sound of the breaking waves, the feel of the warm breeze, the sight of the dazzling turquoise, the taste of the salty air, and the smell of Hawaiian Tropic.

It wasn’t him. It wasn’t him. It wasn’t him.

I’m okay. The girls are okay. We’re okay.

When we made it to the beach, I set up the Shibumi and chairs while the girls unloaded the sand toys. Still, my gazelle ears were raised, as I tepidly started to graze. And though my hypervigilance began to wane with the turning of tides on what was, really, a perfect beach day, the lion’s shadow still had a home in me—still left a sad and mournful mark.

I hope my daughters never balk in a lion’s presence, but, if they do, I’ll understand.

***

Recently, we’ve been re-reading the classic children’s book, Giraffes Can’t Dance, at bedtime.

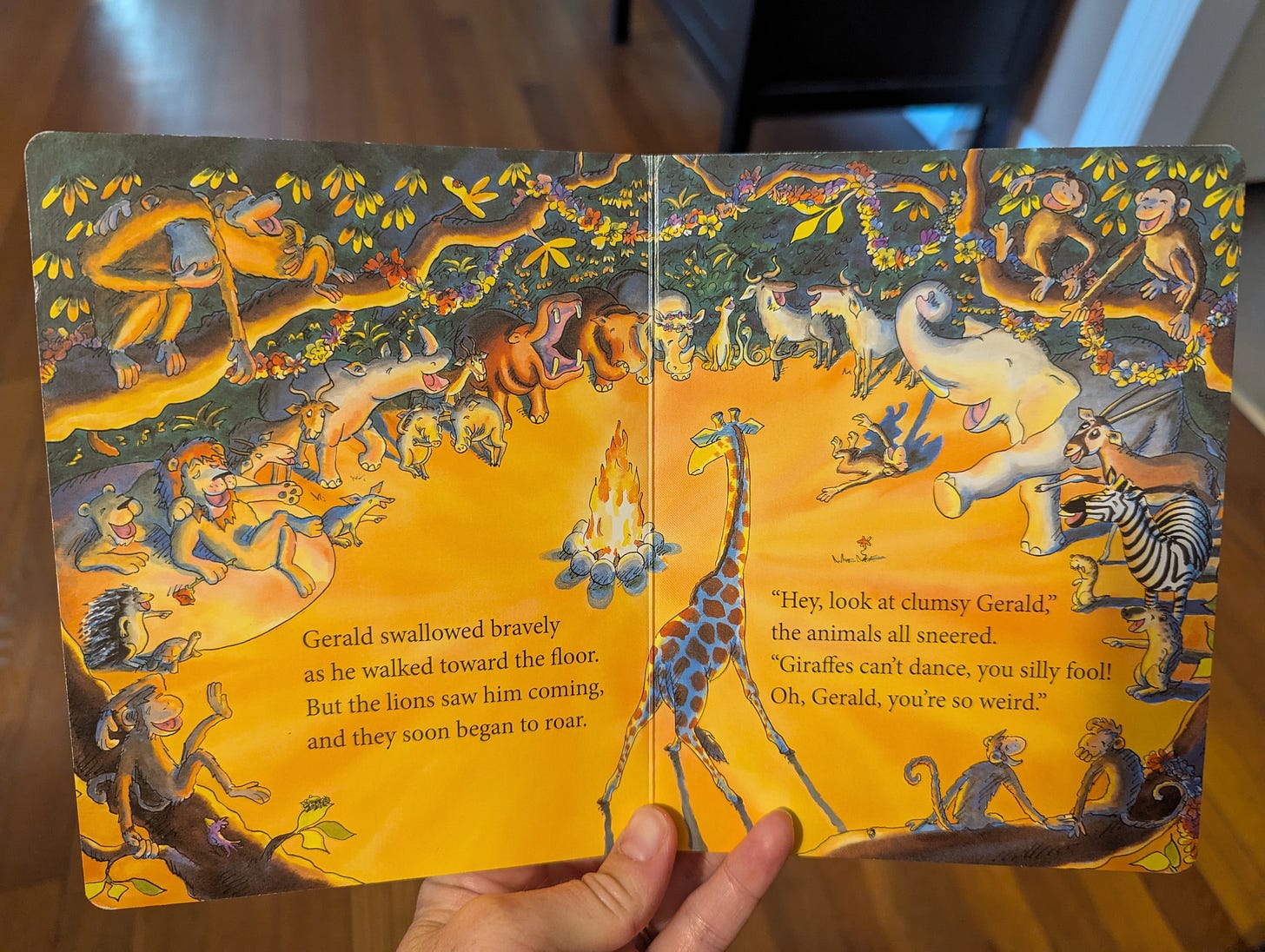

The story is about a giraffe named Gerald who gets made fun of for not being able to dance due to his clumsy nature—with his lanky legs and narrow neck. By happenstance, Gerald is encouraged by a cricket to listen to his inner music, to listen to his body, and dance like nobody’s watching. Gerald then dances, gleefully, in solitude. By the end of the book, he musters the courage to hit the jungle dance floor—surrounded by predators and prey, lions and gazelles (cute, right?), in close attendance—and is met with cheers and applause when he takes his final bow. All the animal attendees ask how he’d learn to dance like that, and Gerald smiles and says, “We all can dance when we find music that we love.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about Gerald lately, about how he shut out the noise and listened to his heart—listened to his body. I struggle to do that as a writer, as a parentified parent—as a human being.

In this modern age, we are met with an ungodly amount of opinion, advice, and, frankly, nonsense. Quite often, my mind, body, and soul require a reprieve because I can’t hear myself. I can’t hear what is true. There are too many cackling hyenas, laughing chimpanzees, and snorting warthogs.

So, yes, my hope is that my daughters will never balk in the presence of a lion. But my additional hope is that, if and when (and, dear God, I do hope never) my daughters find themselves in a situation that elicits a trauma response, they do not later hold anger or resentment towards their bodies’ reactions. I hope they don’t learn to distrust their bodies. I hope they see past their survivalist recoil and thank their bodies for doing what they were ultimately trying to do: protect them.

Today, I thank my body, this delicate vessel, for doing what it was ultimately trying to do during all those years of living in a confusing, unpredictable, and unsafe environment: protect me.

I know I won’t always be there to protect my daughters—this is a sad yet evident truth. But, like Gerald, I hope my children will love who they are and who they become—imperfections and all—and that they learn this much earlier than I did.

Like Gerald, I hope, in their moments of despair, they look up to the sky and “listen to the swaying grass and listen to the trees” and notice, “The moon can be so beautiful.”

Thank y’all so much for being here! If you liked what you read, please tap that little heart below, leave a comment, re-stack this post, and/or consider buying me a coffee or upgrading your subscription. Your participation and support motivate me to keep doing the thing!

I’m running a special offer from now through the end of summer for $12/year ($1/month)! If you feel inclined to support my work with your hard-earned dollars, click the button below! Either way, thank you for reading and supporting my work here on Human/Mother!

P.S. I revised this piece during one of

’s BATWRITES. If you’re interested in writing in the company of some really cool people, click here.

Wow, there is so much here. I'm so sorry about your father, your brother. The scene you conjured up, your dad finding your brother, you're right that that would make just about anyone lose themselves. And that's really what this all is... loss. So much loss. And loss is something I know. I'm so glad you're able to create a beautiful life for your girls where they can be safe and powerful lion cubs. You're so strong, love. So resilient. I'm both glad that you are and sorry that you had to be.

Such a tough series of events to reconcile, Katrina. So well described, but so much hurt there, for your father, and for you. So sorry that your brother died by suicide.

The patterns within families that lead to fear are hard to break, but by making every effort to understand them – recognising the "love tucked into the pain" – you're breaking the cycle. Admirable.