March 6 of this year was what would have been my little brother’s twenty-third birthday.

It’s true what they say about grief: that it doesn’t get any easier with time. You just learn to adjust to your “new normal,” one without a sibling whom you loved unconditionally and helped raise for nearly eight years.

One of my fondest memories of my brother takes place on June 19, 2009, the night before my wedding. The only vacant bed left in my family home was the second twin in my brother’s bedroom. As I waited for him to fall asleep, I began ruminating on what the next day meant for my future and for my family. I—the oldest of five kids—was voluntarily leaving my first loves, my siblings, to start a new life with the love of my life, my soon-to-be husband. I was decidedly conflicted. I didn’t want them to feel as though I were abandoning them; it would have broken my heart if they had felt that way.

And so, I began to cry quietly, while pondering the painful possibility. I suppose my cries were audible because my brother Preston turned over and, in his sweet, squeaky eight-year-old voice, inquired: “Are you crying? What’s the matter?” I told him that I was “fine” and to “just go back to sleep.” But, he persisted: “Trina, I can hear you crying.” And so I told him the truth. I told him how I didn’t want him to think I was abandoning him or my sisters, that I loved them so much that it hurt, and that I couldn’t bear the thought of them feeling sad or helpless after my breakaway.

He quickly replied in that matter-of-fact way of his that is so him: “Trina, we know how much you love us, and we know you aren’t leaving us forever. Besides, I get a new brother, too! That’s awesome!” And then he paused and said in a lower, more contemplative voice: “Just don’t be sad about it anymore, okay?”

“Okay, I won’t be. Thank you, Preston,” I said, as I dried my tears, got out of bed, and gave him a hug and a kiss on his forehead. I then told him that it was time to go to sleep “for real” in my maternal tone.

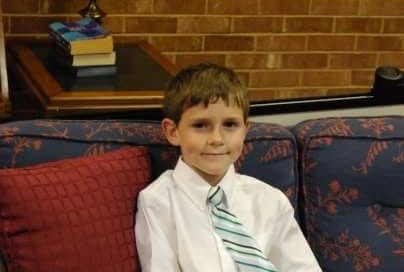

The next day, he proudly served as ring bearer in our wedding ceremony, charming all those who came to watch me and Erik exchange vows. I was so proud of him—so proud of the person he was becoming: a mature, caring, and dutiful individual.

Every year since his passing, I can’t help but wonder on his birthday: What happened to him in his fourteenth year of life?

In particular, I find that birthdays can be just as—if not more—challenging than death anniversaries. Birthdays broach entirely different emotions that are achingly similar in force to that of the person’s day of passing.

On birthdays, you remember their brightness. You remember the joy that was alive when celebrating them. You remember various milestones and rites of passages that the person achieved. You remember their smile, bookended by their dimples. You remember the light in their dark brown eyes, and then you also wonder what exactly it was that extinguished that light.

My brother didn’t make it to adulthood, although he did make a very “adult” decision in the end: he chose to terminate his life at the tender age of 14.

He didn’t get to experience the milestones that come with becoming an adult: first driver’s license, first date, prom, graduation, college, first job, marriage, kids.

Fortunately/unfortunately, he left us, his family, a letter. Its contents meander, a direct reflection of his mental state at the time. The investigative psychiatrist who read it, along with two of his personal journals that were hidden in plain sight in his room, believed that he was in a psychosis and that he was not only struggling with anxiety and depression but also suffered from borderline personality disorder.

We did not see any signs because he was a master at masking them.

Sometime in the late morning of his birthday this year, I shut myself in our bedroom to give myself a moment of reflection, a practice that has now become tradition. I thought about what he would have been like at 23 and asked myself questions that only fed my grief: Would he have enlisted? Would he have gone to community college or a four-year university? Would he have had a “serious” girlfriend by then? Would he have been planning a proposal? Would his silliness have captivated my daughters’ attention? Surely. Would he have taught them valuable skills, like knot-tying? And then my stomach tied itself into a knot, and I felt queasy just by the use of the words “tie” or “knot.” If he gave himself more time, how much longer would he have made it? 23? Until “natural” death? Would any of my hypothetical words or actions have diverted his ultimate decision if I had known the depth of his pain?

I began to moan as a tidal wave of tears surged and found its way out and through my hazel green eyes. I cried loudly, hoping that my daughters wouldn’t hear me. I did not want them to be worried or alarmed. I gave myself a few minutes to grieve and then quickly began pulling myself together. I knew that at any minute, I would need to meet their needs, and I struggled with whether to allow my own needs to trump theirs.

***

Grief in motherhood is such a different experience than grief without children. Before kids, I could afford as much time as I wanted to allow my emotions to spill out and all over the place.

Now, I have to make choices of when and how I grieve because unquestionably, my daughters will show concern, and my eldest, who is almost four-years-old, will begin to investigate my sorrow. She’s quite the detective now and has the vocabulary to boot. Admittedly, I do not look forward to her future interrogation of my brother’s death.

***

I made a quick exit out of our bedroom, recognizing the warning signs of an imminent panic attack. I bolted across the living area to the front door, peering over the couch where my daughters were watching TV. (Cue the mom guilt associated with screen time on top of the mom guilt of giving myself more time to emote.) I nodded to myself and decided that since they were happily preoccupied, I could go sit outside on my covered front porch to orient, a practice that I had recently learned in psychosomatic therapy.

I quietly shut the front door, sat, closed my eyes, and allowed myself to immerse in my environment. The smell of fresh green invaded my nostrils and calmed me. Soft, steady rain showered my front yard, our quaint neighborhood, and the surrounding Appalachian mountains. I opened my eyes and could see fog rolling over the peaks in the distance. Songbirds sang with such glee around me, and their cheerful calls contrasted my own choked-up cries so much so that I cried even harder at the fucking beauty and pain that is this life. The chill in the air made my body shiver at double-speed because I was already shivering from the deep emotion rattling and building and forcing its way out of my body.

After all, it had to.

Nature’s mirroring of my feelings both alleviated and seared my heart wound. Why did he have to leave? He’s missing it all; he’s even missing this: a most mundane yet beautiful moment in the solitude of God’s green, LIVING Earth. I wept for a moment longer in isolation but as predicted, in rapid succession, I was called back indoors to mom-duty.

My daughters were hungry and required an early lunch. I went inside and groaned at the emptiness of our refrigerator. We had just gotten in from a trip to coastal South Carolina late the night before, and we only had a hodgepodge of random food items lingering. I sighed and remembered that I’m the adult, that I’m the caretaker, and that I have to go grocery shopping today, which meant I needed to meal-plan today, too. And then the dominoes started to fall as they incessantly do in motherhood: I also needed to unpack our bags, start laundry, clean out the van, take out the trash from the van, organize the basement because holiday items are in a heaping mess down there, and that meant that I also probably needed to buy the next size up in spring/summer clothes for my oldest, which meant that I needed to go through her dresser and her closet and organize those clothes for storage for my youngest’s future wardrobe, and my youngest also needed to go up a size, so I also needed to pull out my oldest’s size 2T clothes from storage. Insert spiral eyes emoji here.

I took a deep breath in and exhaled out.

The duties of a SAHM are never-ending and, at times, crushing. It’s messy and raw and also precious and blissful. The highs are the highest of highs, and the lows are the lowest. I equate the experience to that of someone who suffers with bipolar personality disorder—only because I have firsthand experience: my father is bipolar, and I can attest to the unpredictable mountains and valleys that accompany the condition.

I began to prioritize what had to be done right then and there and what could be tabled. My most important task was to feed my family, so I made a snack-board of fresh-cut fruit and warm up a glass container of barbecue, baked beans, and potato buns—leftovers from my mom’s wedding reception that was earlier in the week, another celebration without my brother’s physical presence. I felt a twinge of guilt because the food wasn’t the healthiest, but it overrode the guilt of throwing out perfectly good food. And so, I served it to my two little suns.

And then I thought of my brother’s last meal, my mom’s homemade Chinese fried rice, and I wondered if he had thought about how that meal would be his last meal, and if he had given himself more time, would he have chosen something else for his “last supper”?

And then I wondered if my mother wrestled with the same guilt regarding food and nutrition as I do as a mother. I cerebrated “mom-guilt” for a moment and its evolution from generation to generation, and I couldn’t help but also brood over the behemoth of guilt that my mom must have felt as the mother of a son who ended his own life far too early. And, I marveled at how she had survived and had given herself grace, time, and space to move forward and find love again.

I became overwhelmed (again), and I began to shed silent tears as I placed my daughters’ meal on the dining table. They enthusiastically and hangrily busird themselves with eating; I joined them and dissociated.

***

I’m almost four-years-old in “mom” years and almost nine-years-old in “sibling suicide survivor” years, and I still struggle. I thought time would make things easier, but it doesn’t. Yes, I’m learning to cope, prioritize, and balance it all, but it's not an easy task and not one that I believe ever will be.

I miss my brother. I miss Preston. I wish—oh, how I wish—that he would have given himself more time to experience a life that can be hopeful and fulfilling—joyful even.

I wish that he could have experienced my two littles suns: my children. Certainly, they would have adored him, and he—their Uncle—would have loved them wholeheartedly. Without a doubt in my mind, they would have become his suns, too.

I suppose that’s what makes the birthdays of our lost loved ones so agonizing.

We grieve the what-could-have-beens with each passing year that they’re not with us. We grieve the versions of themselves, the versions chiseled and transformed by Time, that we do not get to know because the Sculptor was commanded to voluntarily—or involuntarily—lay down his tool.

The grief is real, fervent, and true—one that is experienced behind closed doors, or sometimes in a public place while wearing sunglasses, or “off-line,” or perhaps scheduled into one’s workweek, or maybe, ever-so-clumsily in the middle of a SAHM’s workday.

Thank y’all so much for being here! If you liked what you read, please tap that little heart below, leave a comment, re-stack this post, and/or consider upgrading your subscription. Your participation and support motivate me to keep doing the thing!

Beautiful and painful. Grief is sneaky and complicated and I love what you said about managing it in motherhood. Thanks for sharing your story ❤️

You are amazing and strong for sharing this story. I’m teary eyed. Truly Sorry for all the pain and sadness associated with your brothers loss.