We’ve been dealing with some real “end times” shit over here lately, y’all.

Last September, Asheville was thrashed with a 100-year flood, thanks/no thanks to Helene. In March, wildfires gobbled up thousands of acres of forest land in our region, extending into South Carolina. Three weeks ago, an insane hailstorm pummeled our neighborhood, leaving our freshly-planted garden battered and our clowder of neighborhood cats terrified. Two days after the cloudburst, we felt the Earth move under our feet, as a 4.1-magnitude earthquake interrupted our slow Saturday morning—I was still in bed, catching up on my saved Substack reads while my husband was snuggled in bed with our two daughters one room over. And, now? Periodical cicadas—basically, locusts—have taken over parts of our small mountain town.

These cicadas are not-your-average cicada; they are of the 13-year variety—Brood XIX—and have been emerging for the past month in thirteen counties of North Carolina, including our own Buncombe County, Cabarrus, Chatham, Davidson, Davie, Gaston, Guilford, Mecklenburg, Montgomery, Randolph, Rowan, Stanly, and Union.

The red-eyed insects are all over our young Mexican sunflowers, our established azaleas and irises, and our weathered oaks and maples. They’re lining our neighbors’ white picket fences, our front steps, our 2014 Toyota Sienna, and our kids’ outdoor toys. Their exoskeletons are finding their way into our homes via the hands of our curious and callow children. And now, after three weeks of their emergence, our sidewalks are littered with their dead bodies. There’s carnage everywhere you turn—crack!—and everywhere you step—crunch! It’s as though nature is screaming: “Look at all this life! Look at all this death!”

During this strange time, it’s been hard not to think about life’s most disdainful fact: our own inevitable death.

And if their physical bodies weren’t enough of a sign of their presence, their sound—loud, whirring, and constant through all daylight hours—reminds you of their long—albeit temporary—occupancy. Like those early days of parenthood, when you think you’ll never sleep again, and then all of a sudden, one day your babe is practically putting herself to bed: picking out and changing into her own pajamas, brushing her own teeth, washing her own hands, wiping her own butt, and choosing her own bedtime stories.

Unquestionably, the stark change in our natural environment has felt like we’ve been living in an episode of the Twilight Zone, anxiously awaiting for that final scene, that shocking revelation, and we can’t help but wonder who these creatures are, their purpose, and why they choose to emerge after thirteen years—why that specific number?

Writing has been… challenging? unproductive? non-existent? near impossible with these Magicicada tredecim sounding off all day, every day. They have been cicadan’ me crazy, and, despite their nuisance, here’s what I’ve learned about these “winged imagines” (with earbuds en place and a lo-fi beats Spotify playlist on loop):

Adults live for 3-4 weeks.

They are basically blind and extremely docile creatures.

Their emergence will last up to six weeks, ending in early June. (God-willing!)

Their above-ground activities center around ‘livin’-it-up’ behavior—a sort of Vegas tear—mating and laying eggs.

The males are the ones who, activating their tymbals, produce the shrill sounds that take up all waking hours of the day in order to attract the ladies.

After doing the deed, the females then cut slits into the trees, using their ovipositors, and lay their eggs in a double row four to five inches in length.

One female can lay up to 600 eggs!

In 6-10 weeks, the young nymphs hatch and drop to the ground, burrow, and feed on tree roots for THIRTEEN YEARS or SEVENTEEN YEARS (if they’re Brood XIII). Yes, folks, these little guys are straight chillin’ eight inches below the surface of the Earth until they're the age of a pubescent middle schooler or a jaded high schooler!

Perhaps though, the ultimate question is: how do they know WHEN to emerge? Well, the answer is not so straightforward. In Meghan Bartels’ Scientific American article, “How Do Periodical Cicadas Know When To Emerge, what scientists have learned is that:

“During their long stint underground, the insects sip at xylem sap, the nutrient-poor but water-rich liquid that moves from a tree’s root tips up to its canopy. Each year as a tree buds and blossoms, its xylem is briefly richer in amino acids, leading one team of researchers to call it ‘spring elixir.’ Cicadas appear to count each flush of spring elixir: when those researchers took 15-year-old cicadas from a 17-year brood and manipulated the insects’ food trees so that they grew leaves twice in one year, voilà—the cicadas emerged a year early, having tallied the required 17 leaf growths.”

So, the sweet, sweet taste of spring is when they know another year has passed, when they are one step closer to being wild and free. However, there’s no real understanding of how the cicadas are logging that critical information—the information that dictates when they’ll emerge and procreate and oh, I don’t know, PRESERVE THEIR SPECIES.

I have to admit that I’m a little jealous of these periodical cicadas. They get a good, long, peaceful rest, and then wake up one day during the most glorious, vibrant season as full-grown adults, bang it out, make babies, and then die.

It seems like a pretty sweet deal compared to this human life that we live: always teetering between joy and suffering, always tottering between love and pain, always at the intersection of happiness and sadness.

***

Last week, while my daughters and I were eating an early dinner, my five-year-old shared a comment made by a classmate at school that day. She said her friend told her that when people get old, they die. (I told y’all we’re dealing with some real “end times” shit over here.)

Her gaze left the food on her plate to find my eyes—her bright blues searching, starting to well with tears, telling me the developing understory: that gruesome reckoning, that heartbreaking understanding of life’s ultimate end.

***

Since our first camping trip of the year a couple of weekends ago, I’ve been re-reading some of my favorite transcendentalists, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Their words have become my preferred mode of escapism lately to—ahem!—keep my mind off the fact that we are very well nearing the end of our days, lest we forget the “end times” events we’ve experienced so far this year.

Not to mention, I’ve found the Internet to be a contentious and cold place, a graveyard of bickering spirits, these last several months—too AI-y, too cult-y, too hot take-y, so I’ve spent a lot of time off-line this month, deleting most apps to make space for what Emerson and Thoreau considered to be more noble pursuits: reading, writing, gardening, forest bathing, and spending time with my husband and our kids.

I was first introduced to the T-gang my senior year of high school in Mr. Harbin’s AP Literature class; his class was one of those formative classes that opened minds and melded hearts. I vividly remember thinking to myself after reading excerpts of Walden and “Self-Reliance,” “These guys are my jam.”

If it’s been a minute since you’ve read my dead white guy buddies, here’s a quick, little refresher:

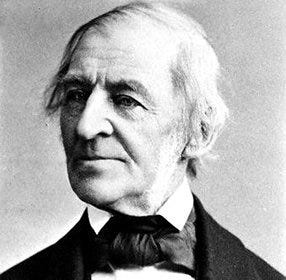

Ralph Waldo Emerson, who went by Waldo, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, 221 years ago, on May 25, 1803—the same year and season as the last cicada double emergence!

From a young age, Emerson knew death. His father, a Unitarian minister, died of stomach cancer just two weeks shy of his eighth birthday. His first love, Ellen Louisa Tucker, died in 1827 of tuberculosis at the age of 20, just two years after they were married. And shortly after her passing, Emerson’s younger brothers, Edward and Charles, died of tuberculosis in 1828 and 1836, respectively. Understandably, these experiences with death played a prominent role in shaping Emerson’s perspective on life—influencing Thoreau, Emerson’s student and friend, as well.

In 1836, Emerson published his famed essay, “Nature.” The piece deviated from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries and communicated his philosophy, transcendentalism, which is the belief in “the inherent goodness of people and nature…while society and its institutions have corrupted the purity of the individual, people are at their best when truly ‘self-reliant’ and independent and see the divine experience inherent in the everyday.”

Thoreau died of tuberculosis, before Emerson, at the age of 44, and it was he who delivered the eulogy at his funeral. Twenty years later, Emerson died of pneumonia in 1882 at the age of 78.

I imagine that Emerson would have recalled this idea that he penned in his essay “Nature” while gazing outside of an open window in his final hours: “For, nature is not always tricked in holiday attire, but the same scene which yesterday breathed perfume and glittered as for the frolic of the nymphs, is overspread with melancholy today. Nature always wears the colors of the spirit.”

These words are hitting me hard today as these extremely distracting cicadas go off. I’m reminded that I’m never truly alone, that life is temporary, that our perspective of it all shifts day to day and nature serves as a reflection of our minds and our hearts.

Better pay attention.

***

As I stared at my oldest child across the dinner table, at the girl who made me a mama five years ago, I was stunned by the passage of time, and how, for the first time, she really “got” death, like really “got” it—like how Emerson “got” it at the age of 8 after his father’s passing.

Up to this point, she’s never experienced the loss of a loved one. She’s never attended a funeral. She’s never even pried into the idea—not even when surrounded by so much death this past month (re: cicadas) or when our dear neighbor died last year. And so, when she broached the subject, it was one of those early life epiphanies—one of those big parenting moments—that even if you try to prepare for the conversation with your little bug, you can’t really prepare for it.

Her somber eyes searched mine, soliciting validation, and I gave it, solemnly, weeping with her as she docked to a new shore: the understanding of our own mortality.

She began to wail and cried out: “I don’t want you to die, Mama! I don’t want to be all alone!” And then my heart shattered into a million pieces because I don’t want to die either, but one day, I will, and one day, she will, too. This is the truth, and it hurts. It hurts almost as much as the real deal.

I picked up my first sun and plopped her on my lap and held her, whispering softly that I’m sorry to tell her that her friend is correct and that we also don’t know when it is that we will die—that information is never given to us. I thought about the cicadas and their peculiar timeline. At that, she gripped my arms as quick as lightning, powerfully, and it was almost as though she believed that the intensity of her tightness—the childish yet impressive might of hers—would extend my time on Earth.

I think it did.

And, I thought: aren’t these sensorial imprints actually capable of lengthening our lives—of making a mark that continues for all eternity, transcending time and space?

An unforced laugh. A warm embrace. A soft kiss. Surely.

Just as the periodical cicadas are able to track the passing of each year, these sensations become our version of xylem, our own markers of a well-nourished life. When someone dies, it is these recordings—these records of love—that translate into essays of grief.

For example, when I learned the tragic news of my 14-year-old brother Preston’s suicide, my mind was the first to reject the information, then came my body—vomiting, retching, collapsing. No, no, no—not him! Not now! No! My heart couldn’t accept my mother’s breathless words over that awful phone call on that ordinary Saturday morning, and it never will because those records still live and breathe within me, still embody part of my soul.

The feel of his dewy skin.

The texture of his wiry hair.

The twinkle in his dark brown eyes.

These are just a few of the artifacts, of the evidentiary pieces, that his physical body once existed, once trudged this perplexing planet, and they will never die—as long as we—as long as I—keep writing about him, keep speaking about him until the next generation of tellers picks up the baton.

As Emerson wrote in his essay “Nature”: “Nothing divine dies. All good is eternally reproductive.”

In that poignant moment, my heart expanded to its full size, cresting at the point of overflow, and I was simultaneously heart-broken and heart-woken: to be loved so is to have lived so.

I told her that I loved her with all my heart—something my mother has told me since I was a baby, something that her mother told her since she was a baby. And then I told her that that’s why we try our best to choose love at every opportunity we’re given because we never know when it will be our last.

“We’re not perfect,” I declared. “But we can try.”

“Loving is living,” I said, my voice cracking. “And the most remarkable thing about love is that it lives ‘times infinity’ (a phrase she’d recently learned), lasting well beyond our lifetimes. Isn’t that pretty amazing?” I asked her, to which she quickly replied, madly wiping away her tears, “Uh huh. Hey, Mama, can we play a game together?”

I replied, “Yes.”

And, we did. We played Jenga with her little sister, and we laughed and were in awe of the three-year-old’s impeccable dexterity. I congratulated my second sun on her well-played moves, and I recognized that this moment is its own recording in the making of our lives similar to that of the dormant cicada nymphs yet to emerge from the subterranean, similar to that of Emerson with his children in his home in Concord, Massachusetts.

The weight of my children’s bodies in my lap, distinct and different from their first-ever recorded weights, made me ache for a time gone by too quickly and too slowly.

Looking out of our big bay window in our living room, I immersed myself in the smell of their clean hair, the feel of their smooth skin, the sound of their infectious and individual laughter, and I thought: parenting is transcendental—an experience like none other, where one leaves one dimension and enters a new one via the pat of a bottom, the snuggle-puggle of a cheek, the cozy-wozy of a body nuzzle, where one passes down that same ancient God energy that has been given by caretaker and received by child, imperfectly, for centuries.

I wouldn’t trade it for a cicada’s life for anything. No, this life—this human life—is my preferred existence, death and all.

“To speak truly, few adult persons can see nature. Most persons do not see the sun. At least they have a very superficial seeing. The sun illuminates only the eye of the man, but shines into the eye and the heart of the child.”

–Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature”

“We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep… Every man is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour.”

—Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Thank y’all so much for being here! If you liked what you read, please tap that little heart below, leave a comment, re-stack this post, and/or consider buying me a coffee or upgrading your subscription. Your participation and support motivate me to keep doing the thing!

CICADAS!!!!! those things were nuts

Woven so beautifully together I almost forgot we’re considering life and death in this! Thank you Katrina 💖🙏🏻