Snake Night

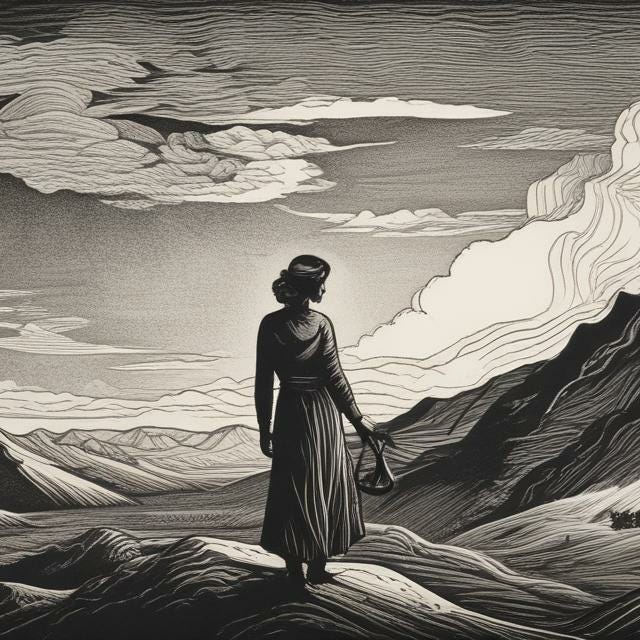

A recollection of a traumatic childhood memory and how I'm stepping into my power.

For the month of May, I kept catching my four-year-old daughter singing The Sound of Music’s “Do-Re-Mi” in preparation for her preschool’s end-of-year program. Hearing my oldest’s sweet voice croon the catchy tune warmed my heart. I didn’t expect or anticipate the emotional hurdles that quickly followed.

I wasn’t prepared for the sadness I felt, for the song marks the end of her first year at Montessori school and is yet another marker that my first child is no longer a baby or a toddler; she’s a little kid now. I wasn’t prepared for the joy I felt, as I repeatedly heard her incorrectly belt the line: “a TROPICAL of sun!” instead of “a drop of golden sun!” I wasn’t prepared for the anticipatory grief I felt, knowing that one day, in the not-so-distant future, her errors would be corrected, and that last remaining and most endearing toddler trait—the incorrect recitation of words or phrases—would dissolve.

As parents or caretakers, are we ever prepared for these feelings?

Moreover, I wasn’t prepared for how this bittersweet time with my daughter would also be a triggering event. I didn’t expect that the simple and subtle singing of a song would open a floodgate of childhood memories. At first, warmth and endearment came pouring in and then out gushed trauma and sadness.

***

Julie Andrews was the “movie mother” that I had always wished for. Mary Poppins, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and The Sound of Music were among my favorite films as a child. They showcased Andrews’ charm, talent, fun-loving nature, and tenderness and were the reason I routinely borrowed the VHS tapes from my local library.

Ironically, my Julie Andrews-era began in the small, rural town of Andrews, South Carolina, whose claim-to-fame is being the home of “Chubby Checker,” the charismatic and magnetic inventor of “The Twist.”

I remember my Papa—my mom’s dad—would often impersonate Chubby during this particular stint of my childhood. He’d twist his hips in perfect rhythm and let out that good-time-havin’ cackle of his, accompanied by one of the brightest smiles that I have ever known–one that rivals even my own children’s smiles. His easy ability to invite anyone and everyone, including McDonald’s drive-thru workers or the cashiers at Piggly Wiggly, to join in on the fun, to release their worries for a minute or two, is one that I sorely miss. I wish that my daughters could know the magic that was my Papa, their great-granddaddy.

My family and I lived in an ugly, faux-wood trailer off a dirt road, just two doors down from my dad’s oldest brother, who died from an overdose in 2022. My Granddaddy Benton—my dad’s dad—owned the property, and my parents paid him rent that was dirt cheap, which was a fair rate if you considered the plot of land that the brown rectangular prism sat on: a desolate landscape, uneven and dry with patches of lifeless grass in places and clumps of red clay in others.

The quality of the land told the story of the quality of life within, one that was drought-stricken and desperate for attention and care.

My bedroom was located on one of the far ends of the trailer. I had an old, secondhand Victorian-style four-post twin bed that my mom painted soft pink in an unwieldy attempt to distort the reality of our financial situation to any potential visitors. Additionally, I had an old dresser in my closet with a box television and a VHS player housed on top.

This is the room where I was often transported to a warm and loving place, a home different from my own, thanks to Julie Andrews. I remember considering that if my 23-year-old mother could act or sing like her, then maybe, just maybe, she, too, could warm my 25-year-old father’s icy center—just like Maria melted the Baron’s cold heart in The Sound of Music.

Beyond our backyard were fields of tobacco, soy, and corn, the perfect playground for small children and tiny creatures.

One particular harvest season, whenever I was in the first grade, I remember the maddening infiltration of field mice into our home. I remember the sound of mousetraps popping off in the middle of the night as temperatures began to drop. I remember feeling petrified of the pocket-sized critters after having vivid nightmares of waking with a real “rat’s nest” on top of my head, a term often used by my mother to describe my morning bedhead.

One fateful night, horror became reality.

In the wee morning hours, I woke up to a long, drawn out hiss, coming from my closet—just a few feet away from my bed. The chilling sound sliced the deafening silence of the pitch-black room. In record time, I mustered what little courage I had as a six-year-old scaredy-cat and shouted, “Mom! Dad! Come! Quick! Hurry!”

Within seconds, my parents burst into my room, flipped on the light switch, and surveyed the scene. I signaled them to stop and listen, vigorously pointing my finger towards the closet. My dad inched his way towards the source and quickly discovered the maker of the surreptitious sound: a copperhead. The venomous viper was in the middle of chowing down on a field mouse that had made its way in—a mouse that had sought refuge from the combines and the cold.

Instinctively, my dad ran out to retrieve a shovel, my mom a black garbage bag. When my dad re-entered the room, adrenaline coursing through his nervous system, I noticed an unfamiliar look on his face. Fear? I wondered. Without a hitch, he lured the red eye into the plastic den and, with zero hesitation, whacked the snake with such a force that I nearly jumped out of my own skin, mentally noting the similarity to how the limbless reptile sheds its own skin that allowed itself more room to grow.

The serpent didn’t stand a chance against my dad: it was motionless, slain, after one heavy blow.

I remember the look of relief on my mother’s face and her muttering these words to my dad: “If that snake would have bit Katrina, I don’t know what I would have done…” She choked on her words, exhibiting intense emotion, and my dad nodded, understanding her fear. They, the people that had brought me into this world, stood before me both visibly shaken. They came to my bedside and embraced me as though their worst nightmare had materialized. Their strong squeeze clued me on the gravity of the situation, and I shivered in their arms, relieved.

Nonetheless, the next day, I remember feeling conflicted about what I had witnessed. On one hand, my father had protected me; on the other hand, my father had shown what he was capable of: killing.

My fear of him grew.

***

Not long after “Snake Night” (as the evening had been coined by my family), my dad came home in one of his “moods,” except this time, the atmosphere felt different. This time, his erratic behavior and speech made every hair on my skin stand tall, a by-product of the friction building between my two parents.

My child-brain collected, sorted, and synthesized the information in front of me: my father was exceptionally upset because he believed that my mother had been cheating on him (even though she, my baby sister, and I had spent the entire day together at home). Not to mention, we spent every day together. She was a stay-at-home mom of two daughters and had no extra money to spend beyond gas and groceries, which was mostly covered by WIC and food stamps anyway.

It turns out that my dad had completely fabricated the story, created the drama, so that he could cast himself in the leading role: a sympathetic victim of a “wicked woman.”

In order to “get the truth out of her,” he began his rampage by stomping through our 90s-floral-wallpapered aluminum can and cherry-picking my mom’s most cherished and beloved home decor item: a Victorian-style lampshade.

With a gruff and decisive placement, he put the lampshade on our “breakfast” table (though it was also the place where we ate all of our meals). Then, he marched into my parent’s bedroom to retrieve one of his golf clubs, a recent gift from one of his evangelical minister-friends to encourage and endorse my father’s “godly calling.”

When he returned to the kitchen, I saw the same look in my dad’s eyes as I had seen on “Snake Night.” And then it hit me: it wasn’t fear that I had seen, it was mania. He paused, locked eyes with my mother, and asked her “once again” if she had been “messin’ around.”

Shaking from head to toe, my mom shrieked, “Of course not. I would never even think about doing something like that. I am committed to my commitment—to you.”

And that’s all he needed to wreak havoc: a “lie.”

He began annihilating the lampshade, shredding the satin fabric and bending the frame with every blow. He kept shouting in his raspy, monstrous voice, “See? See what YOU did?” I glanced at my mom, noting the submissive curve of her back and her hot face buried in her pale hands.

“This’ll teach you,” my father said as he gave one final whack to the obliterated shade.

In an effort to elevate and conclude the final scene of his performance, he maneuvered the golf club atop the refrigerator and swiped the potato plant from off its stoop. He growled, “Now, if you would have only told me the truth from the very beginning…” As the pot landed on the kitchen floor, its dirt splayed dark brown across the laminate tile. Its presentation reminded me of histosol, the type of soil found at my dad’s mother's gravesite several miles away, located under ancient oak trees adorned with the distinct gray moss of coastal Carolina. We visited her once before, although I had never actually met her. She died at the age of 49 from esophageal cancer when my father was 16.

Teardrops of despair flew from my mother’s eyes, and she begged my father to “just calm down” and to believe what she was tellin’ him. She wasn’t “runnin’ around with nobody.” She reassured him that she was married to him and only him.

(It should also pointed out that there was never any mention of love throughout this entire debacle.)

“Please, stop. Please. Not in front of…” she whimpered, glancing in my direction.

I was standing in the middle of the living room, adjacent to the kitchen, frozen, holding my breath as my body recorded the trauma. I couldn’t move my legs; they were heavy and rooted like the trunk of the great oak tree that divided the property line between our house and my grandfather’s dilapidated childhood home: a haunting symbol of a self-fulfilling prophecy passed down from one generation to the next.

I was paralyzed because I feared that if I’d move, I would lose it all. I’d lose my innocence.

My mother turned and motioned me to go back to my room with a look on her face that made a lasting imprint on my hippocampus. Her expression was one that I had not seen before, one that I could not translate. In that moment, I remember feeling like I had failed her for since the time I was born, I had been trained to read and respond to her body language with superior fluency.

Nearly thirty years later, I now recognize her face as the face of fear, guilt, shame, and hopelessness—all wrapped into one. Through therapy, I’ve also come to acknowledge that it was around this time that I began to really know, understand, and befriend these emotions myself, of which have now become “old friends” with whom I greet with familiarity and speak to with curiosity: a necessary and healing exercise.

After a beat of unresponsiveness, my mother commanded me a second time with a frantic, stern voice that suggested that if I didn’t listen, matters would become worse–for her and for me. And though I was an obedient child, I delayed her command for as long as I could because I was genuinely fearful of her life.

I had remembered what happened on “Snake Night.”

My dad, enraged by my mother’s diverted attention, grabbed her biceps, turned her body, and forced her into their bedroom, located just off the kitchen. He slammed their door and continued spatting stinging invectives at her in a voice that rattled our trailer, a voice that became the voice of my childhood, a voice that I have attempted to erase from memory (and also through estrangement) yet still haunts me to this day.

He continued to blame her for his violent actions, for causing him to frighten a young child, and for attempting to destroy a sacred covenant: their marriage. And although I was young and inexperienced, I understood the gravity of the situation, of how my mother was cornered now. I feared that my father would hurt her—maybe even off her—just as he had done the copperhead.

But he didn’t. My mother survived that day and another 11,000 days thereafter.

It took nearly thirty years of an abusive marriage, losing her son—my little brother—to suicide, and losing her parents to health complications for my mother to gather the strength and courage to cut ties with her narcissist husband who just so happens to be my father.

God bless her; she’s loyal to a fault.

She finally chose to thrive rather than to simply survive.

***

Though my daughter’s singing of “Do-Re-Mi” was an unexpected trigger, it lended me the opportunity to make space for hope and healing.

This is both the catastrophe and the miracle of bringing children into our world. They inexplicably open old wounds and mightily mend them at the same time, despite their innocence and size.

How lucky are we to have been given these most transformative gifts, these most precious being, that give to us in all different ways for all these days?

In capturing these new, tender memories with my daughter, like this special introduction and singing of “Do-Re-Me,” I’m reminded of this undeniable truth: we are the writers of our own stories.

Great power lives and resides in each of us: a power that can modify any element of any story, that can hijack any plot, and that can pen any ending it chooses, maybe even one that is happy.

In the end, it's up to us to step into our power.

Thank y’all so much for being here! If you liked what you read, please tap that little heart below, leave a comment, re-stack this post, and/or consider buying me a coffee or upgrading your subscription. Your participation and support motivate me to keep doing the thing!

Thanks for stopping by to read and give my essay some love, @Danielle and @Ingrid! ❤️

Wow. What a story. That’s a whole lot to take in from one post. Thank you for sharing your story. I love your daughter’s tropical sun words. Those are adorable!

Once upon a time, I was a camper at sleep-away camp. And a copperhead was outside our cabin. Somehow, the director got notified (maybe we called out to the next cabin for help?) and the director came with a shovel.

He didn’t kill it in front of us the way your dad did - though I figured out later that must have been what he had done with one fell SWOOP of his shovel behind a nearby tree.

Your dad doing that in front of you, instead of taking it outside is terrifying. That’s a way to show dominance.

I am also willing to bet money he was cheating on your mom and attacked her because he couldn’t fathom that she wasn’t. That’s very sad. I am so glad she finally got out & that you are in therapy. I hope your mom is, too. She’s had a lot on her plate.