Human/Parents Interview: Mills Baker and Suicide Grief

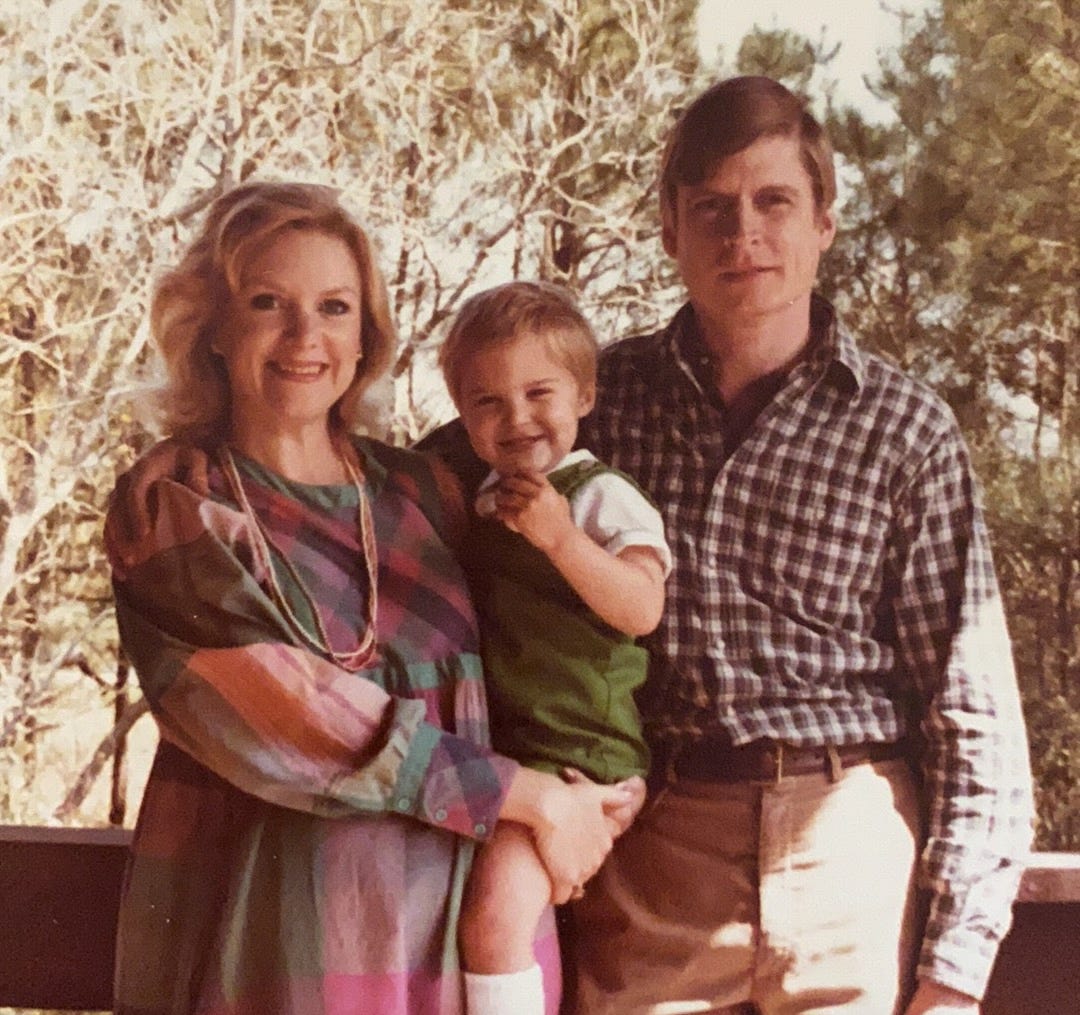

Human/Mother welcomes a very special guest: Head of Design at Substack, Mills Baker!

Human/Parents is an interview series that explores and illuminates various mental health topics that some parents face while simultaneously performing the most important job on the planet: raising the next generation. Guests are Substack creatives who are also parents dealing with one or more of Human/Mother’s rotating monthly mental health topics.

This month’s topic is suicide grief.

So, pour yourself that third cup of coffee, snuggle in, get cozy, and get ready to meet our next guest:

, Head of Design at Substack and author of Rats from Rocks!Hi, Mills! Thank you so much for being here. I understand that this conversation isn’t the easiest, but I feel that it is important to have these conversations and publish them because there are humans out there—like us—dealing with the same kind of complicated grief. My hope is that through this exchange of words we can help others, particularly those who are also parents trying to raise the next generation of humans, feel less alone.

Before we get into it, tell us a little bit about yourself. Of course, many of us know you as the Head of Design at Substack, but, for those who don’t follow you or subscribe to Rats from Rocks (as they should!), let us in on who you are, where you’re from, what your family looks like, etc.

Sure, and it’s my pleasure; as difficult as the subject may be, it’s also a strange burden not to talk about it, especially as time passes. It feels like an omission of sorts; I often find myself wanting to tell people about the deaths of my parents because not to do so is to leave myself unexplained, maybe, or at least incompletely accounted for.

I’m a 44 year old man; I live in my hometown of New Orleans with my wife, Abby, and my two children: Keziah and Raines. I previously lived in San Francisco and the Bay Area for more than a decade, and I lived for a few years in rural New York while attending (but not graduating from) Bard College, before I moved to Baton Rouge and finished college at Louisiana State University, majoring in Philosophy/Religious Studies.

I do indeed work at Substack, managing the (phenomenal) design team here; I’ve been here five years, and previously had roles in software design, management, and product management at Quora, Facebook, and some startups. Before that, I worked in a call center for five years in Baton Rouge, and before that, at a veterinary hospital. I was a musician in my youth.

How did you find writing, or—maybe rather, how did writing find you?

I’ve been writing for so long that it’s hard to give a precise accounting, but I know my parents are to credit or blame: both were creative and literary, read a great deal, and encouraged my habits in this domain. I got online in the mid 1990s, and due to infrastructure and technology limitations, all there was to do at the time was write; online journaling was the original “selfie”! So I’ve been posting text since then, through college, just for my entire adult life.

I’m really a writer because I love and value what I read; I mostly write in reaction to, or as an extension of, what I encounter in reading. I’ve found novels in particular to be a primary means of sense-making, but philosophy and religious texts too; for better and worse—truly both—I experience life very textually. My father liked to quote Logan Pearsall Smith: “Some people say life’s the thing, but I prefer books.” I’m not quite so far along that axis as he was, but it’s close.

In “Mother,” you wrote about your mother and her struggles and you also shared in that same essay that your father took his life in 2021. You said that your father was open with you and your mother about his plans to end his own life. I don’t know anyone who has had that experience, and I’m wondering what was that experience like for you?

It probably goes without saying, but the word “intense” comes to mind. Both of my parents felt horror at the prospect of recapitulating their parents’ ends: long senescences, years of diminished capacities, a gloomy twilight of watching television while degrading mentally and physically; I think they experienced these periods with their parents as among the most depressing and frustrating experiences of their lives, for a mix of reasons. Some of those reasons struck me as superficial: for example, their exasperation with the “waste” entailed by costly medical or residential services that didn’t produce much “quality of life.” Others seemed very relatable, though: the transformation of people they knew into bed-bound and absent and angry and terrified shells of themselves upset them as it would anyone.

So for many years, I’d known that neither intended to allow this to happen to them. As they aged, they communicated as much with increasing specificity, until one year I was suddenly talking to them about suicide, conversations which continued periodically for years amidst regular chats about books and friends and so on. Both of them were rather steely about it all, or at least didn’t disclose any anxiety or emotional upheaval about it to me. It was simple, in their telling: they didn’t want to live indefinitely; they didn’t want to live “too long”; above all, they didn’t want to live past the point of remembering that they didn’t want to linger.

This part of it was easy enough to understand. I didn’t want either to die, but I was proud to have grown into someone they could talk to frankly about these things, and proud that I could balance to some extent expressions of my love and interest in their continued survival with expressions of comprehension and support, if not approval.

The more complex part is that in both cases, addictions played a part. My father, a high-achieving and scholarly man, was prescribed—irresponsibly, in my lay opinion—benzodiazepines for late-life insomnia. Anyone interested can read about the not-uncommon trajectory these drugs sometimes entail; he eventually wound up in a state where he needed more of them than he could take and still couldn’t find relief, while their side-effects made life unbearable for him. I advised him about this, and he accepted it, but also—I argued because of the drugs, he disputed this—felt that quitting them would be too awful an experience, he felt that he was at the end anyway. He said he felt happy with his life and that his race was run, and he wanted out. When he stopped being able to read, he called me to let me know it was imminent, and one morning, he shot himself in the head at his desk, dying instantly. There was no exit wound, and my mother found his expression “peaceful.” I attribute his death 75% to benzodiazepines and 25% to his prior determination not to endure decrepitude, but the exact percentages were a matter of debate, and I try not to get hung up on the preventable causes in light of those that were fixed regardless. (I could also e.g. note that lockdowns destroyed his daily habits and surely contributed to a sense of isolation and depression).

My mother’s case was somewhat worse: she was an alcoholic, and in her final years was sick in the way that lifelong alcoholics get, just metabolically “shot.” She suffered a stroke that robbed her of effective hearing, and as someone who lived for social exchange and conversations with strangers, there simply wasn’t much left for her; she lost herself in a lonely maze, it seemed to me, repeated herself, wasn’t able to extricate herself from her misery and confusion. She attempted to die by not treating an infection—a method I warned her was likely to be as physically excruciating as any—but failed when a neighbor found her collapsed outside and took her to the ER, where she came to in a fury. She then decided to starve herself to death, and did. It took a while and was quite hard to witness; I visited her as she passed into unconsciousness, thrashed and moaned, and eventually passed away. I had promised not to intervene, and I didn’t.

I periodically felt very disturbed by these processes, the conversations, the practical temporal happenings, but I tried to stay grounded. Parents die; the manner isn’t the main thing, and indeed as they often remarked almost all ways of passing are brutal in one form or another. They warned that “children always feel guilt when parents die,” about moments missed, about things said or unsaid, etc. They told me to remember that they didn’t want us to feel guilt, even if it was inevitable. We’d had a rare gift: every imaginable conversation before their departures, every exchange one might want to have with one’s parents before they go. They knew how I felt about them; I knew how they felt about me, about themselves, about life and death and everything else. Many people do not get this.

I mostly let feelings come and go, focused on “doing what they’d said they wanted us to do,” and tried to keep the frame larger than “the incidents”: this is life on Earth, after all, and the end is not more important than any other chapter. They did their best, made their decisions, and sorting my feelings about it all was for me to do in the fullness of time.

After your father died, what was that initial experience of grief like—what do you remember about that time?

I knew the day before that it was likely to be very soon, as in our last phone call he sounded like he was already heading to another shore: distant, hollow. I was in California and he was in New Orleans, as he’d asked me not to move back for his sake. I was forty years old and had a newborn baby girl. I felt stricken, but purposeful: I had logistics to sort immediately, and had as mentioned discussed it all so much with him in the months preceding that there was even a sense of relief. For weeks I’d lived with the knowledge that it was coming and the doubts and anxieties about what should be done: should I ignore his wishes and e.g. have him committed, at 77 years old, to try and force another chapter of life? Did I know better than he did about how the end of life should go, or about his own prospects? How would he do it, and when? All of those questions suddenly resolved. I cried, I traveled home, I found mom in a state similar to my own, I arranged a funeral, I talked to his friends, and I mourned. I read books from his library and wandered around the city with my friends, who knew and loved him. We reminisced about his sharp, dry sense of humor and shared stories from our time with him.

How has your grief evolved today?

It’s grown subtler and simpler. With suicides in particular, there’s some period of wrestling with the particulars and the complexity, a reflective period of counterfactuals and interpretations, but eventually in my case as I expected that all got quieter and was replaced by the straightforward experience of missing him (and later, her). You know, the ordinary stuff: I wish he were around! I wish she could see this or that (for example: New Orleans got snow, a huge amount of snow, and she’d have loved to see that), I wish I could call them and talk to them like I used to!

My room is full of their things; I’ve started to dress as he did, more formally and traditionally, and somewhat self-consciously try to do things that she did, like take walks around neighborhoods just to observe and imagine the lives of the people there, etc. I catch myself ordering what I think they’d have ordered at restaurants. I enjoy exploring their interests (in music, in art), enjoy looking at old photos of them. I think of them both often and try to honor them, so to speak, in various kinds of choices and behaviors.

You shared a great deal about your father in “Father”, and, at the end of your essay, you wrote that you missed your father:

“I do. I talk to him in my head all the time. Occasionally it’s quite unbearable, hollows me out, seems to break something inside me that much depended on. At other times it feels like some variation on phantom limb syndrome, as though when someone is a structural component of your self, you simply will not stop sending signals back and forth, feeling their presence, relating to them. I’ll confess that sometimes the intensity of the feelings it catalyzes is almost thrilling; thinking about my father feels like touching the void; it feels as though I could “fall in” somehow, perhaps die myself merely by immersing too deeply in his death. Sometimes this has a very visual quality: I will imagine him at his desk that morning and feel as though I’m falling into his mouth, hearing a scream or a gunshot as everything turns black.”

You published this piece in November of 2022, and I’m curious when you think of your father now, what is it that immediately comes to mind? What do you miss about him now?

Well, I don’t have that feeling anymore, I can say that; I don’t hear the “howl” of grief, of oblivion. I regard his end as “sad,” even “especially sad”—our family was greatly harmed by addictions, but had somewhat made it through the darkest years, and for them to have fallen at the last hurdle is tragic—but I don’t feel as though I might be consumed.

When I think of him now, I wish I could hug him or talk with him about the subjects that interested both of us. I think he’s in a better place now, and I feel the peace I think he feels; I feel it in the sky; I feel the clarity of that peace in the sky and in the grass.

I interpret a lot of the visits I get from lizards and dragonflies as visits from them. So I guess I feel some sadness, some warmth, some fondness, and then periodically a sense of disbelief: I just can’t believe it all ended as it did.

Were there any resources or support groups that were particularly helpful to you in those early stages of grief?

I didn’t really avail myself of anything, if I’m honest, beyond my regular friendships and sources. I don’t want to suggest this is “the right way,” of course; I’ve been in therapy for decades, have been as deep into support groups and counseling as one can get, so I’m already roughly familiar with what such systems do and do not accomplish, and perhaps can self-administer some of that. To be honest, I didn’t want to map them or this experience to anything formalized or general, didn’t want to over-weight the manner of death relative to the fact of death. I’ve had prior experience with suicides in my personal life and indeed have been suicidal myself, and didn’t feel much need for structured analysis or interpretation; I wanted to be present with myself and with them and their lives, rather than to think about symbolic or conceptual frameworks or processes or issues like “healthy” vs. “unhealthy” grief or what-have-you. It just didn’t feel like that’s what I needed.

I’m religious, so I prayed a lot and wished them well in the hereafter.

You’ve shared with me that your wife’s father also died by suicide. I’m curious when you learned that information (while dating, when married, etc.), what that experience was like (finding a painful commonality between one another’s histories), and if that news spawned conversations about one another’s mental health and/or any concerns of your children’s mental health?

My wife’s family is unfortunately rife with suicide, and I believe we discussed it the first time we talked; I may have known it beforehand, too, from her blog. As she and I often marvel, when we met, it was she who possessed the “suicidal and addicted family,” whereas my family seemed robust and well-ordered (to her, at least; I knew the reality); but just a decade or so later, it was my parents ending their lives and my family falling to pieces, while what remains of hers has been doing well. I regard her father’s suicide as significantly more tragic than those of my parents. He was in the prime of life and was felled by a relapse into alcoholism; if he had not been drunk, it wouldn’t have happened, which makes it in some senses as much an accident as anything else. He’d have been very happy with how her life has developed, and it’s an awful shame that he’s not here. It’s also sad that my parents aren’t here, but their judgements about not wanting to live “too long” have at least some defensibility or validity, so it’s categorically very different, and this is reflected in how we experienced these things. She is still, many, many years later, in pain about her father, conflicted, troubled by it; her grief is more complex, as they say.

At the time I learned of it, I suppose my main reaction was that it sounded to me that her life, like my own, was complicated! I felt for her, but didn’t draw any particular conclusions about it beyond that: I suspected she knew how hard life can be and how often our demons trouble and even get the better of us.

Where have you both landed with your family history and/or mental health concerns? (Just FYI: my husband and I had always planned to have children, but after I lost my brother to suicide in 2015, I questioned whether or not it was wise or reasonable to start a family. I wrote about it here.)

Well, I didn’t hesitate to have children. Beyond the suicides and addiction, my family has copious heritable problems, not least of them being reflected in many generations with what’s presently called “bipolar disorder.” Candidly, this doesn’t mean that much to me. I’ve been happy for a lot of my life; I’ve had moments and experiences of joy and elation; I’ve been part of good things. I’ve had all the rest, too, the things that might make one hesitate about reproducing, but I am not especially persuaded by normative thinking about any of this. No one knows what life is “about,” or what makes it “worth living” or “not,” or what will lead to good or evil on Earth. All we have to give our children is a ticket to this ride, so to speak, and then our best efforts at equipping them for goodness and its prerequisites: health, happiness, wisdom, and so on.

This planet has always had more than enough pain and suffering that it would make sense to doubt whether one should have children, and more than enough joy and thriving to suggest that one should. I of course worry for our children, but I’m glad I was born, and know that my parents were glad they lived, and didn’t find any of the stumbles or lapses or mistakes or tragedies sufficiently overwhelming, in light of all that’s happened in human history, to change my mind. If it comes to ill, perhaps I’ll regret it, but regret is also part of life. There’s nothing for it; there will be no safety for us here; there is no “reasoning or working our way to an easy existence”; and there’s nothing for us but existence here. So we rolled the dice and have so far loved it, and the kids seem glad to be around to make messes and learn about animals and dance and all that!

Have you thought about when and how you’d tell your kids about their grandfathers’ deaths, and what that talk would look like/sound like? (To be transparent, I’m also pondering these things when it comes to talking about my brother—he killed himself at age 14 in 2015—and I’m just curious how others are approaching the subject matter.)

I have, but have made no progress! I have not told them that they were suicides. I try to be honest with them wherever possible, but I am aware that “knowing about the possibility” has “social contagion” dimensions. I expect that at some point, the fact that it’s public knowledge will force conversations, and I expect I’ll say something like this: my parents loved life, loved their family, loved their experiences, but were afraid of suffering and decrepitude, so they chose to die in their late 70s before they lost the strength to make that decision. I think it was the wrong decision, because I think they both might have lived meaningfully longer, and needn’t have feared suffering so much, but none of us can say what old age will look or feel like before we’re there. I regretted their decisions, but tried to respect them out of fealty and a sense that they had reasoned about them for many years; that I think they were mistaken doesn’t lessen my respect for them, but I hope not to do the same and I hope you won’t either, etc.

About Abby’s father, I’ll likely emphasize that alcoholism and drug addiction run in our families, that sobriety is important for a peaceful and good life for us, and that had he not been a drinker, he’d be alive today, and would have loved being present for their childhoods.

In sum: I won’t keep it a secret forever, but will delay the conversation with the idea that every passing year increases the chances that they can understand it all “properly” or “safely,” and I’ll hope to provide interpretations that are accurate and fruitful for their own decision-making as they deal with all these dynamics in their own lives.

Given what I’ve read about both of your parents and your relationships with them, I want to know how do you remain so hopeful—so forgiving—and positive?

I think that you can sort of reason about this in reverse: to be hopeful, forgiving, and positive leads to a happier life, a life in which one has the strength to be good; being good to others and fulfilling one’s duties according to one’s deep beliefs and principles seems to me the best way to go through life, whatever comes. I happen to have the (possibly Panglossian) belief that “the good tends to work best,” or that “what works tends to be the good,” so I try to arrive at the good however I can, without of course wanting to warp the truths of life or distort or suppress my own feelings. A lot of this is made easier by both Buddhist and Christian beliefs, but you can get to most of it any which way, I think.

If one wants to be hopeful, forgiving, and positive, one must try to work out how one might be so: what ways of thinking about life can yield these states. For example: my mother was mentally ill and abusive. One can take that very seriously and “blow it up,” so to speak, to be the entire picture, and one can obsess about the “damage” it did, and so on. Of course, one can also situate it in a global and historical frame: it’s likely that I had less of this “damage” than most people had as a matter of ordinary life 1,000 years ago, and many of those people were not destroyed by the traumas of e.g. seeing many siblings die, experiencing famines and plagues, etc. It is possible to change how one experiences the world; we know this from countless examples of people doing so. The process for me has involved a lot of holding multiple frames in mind: I have compassion for myself as contemporary theories of mental health suggest I should, but I also contextualize those theories as being “just one way of thinking about things,” alongside others which minimize the import of that entire frame, and even suggest that it’s silly or insubstantial! You don’t have to choose one way of thinking about things. My mother was, in fact, a luminous and loving woman who was also capable of great evil. My father was, in fact, a happy and erudite family man who did his duty and also gave into a ludicrous pill addiction that prompted a gunshot suicide.

Maybe the summary is: when I look at the world through many lenses, I see ample cause for being hopeful, forgiving, and positive. And I see that people who are not, often destroy themselves, cut themselves down, partialize themselves in a fruitless effort to escape pain, which cannot be escaped and which isn’t the whole story, in any event; pain is less of a threat than hopelessness is, I am very sure. I may someday lose even the ability to be hopeful and forgiving and positive! I do not want to require conditions; I do not want to index solely on feelings; I want to think about what I perceive as “the good,” in individuals and parents and spouses and neighbors and friends, and live with that as the animating energy behind me, while having patience for myself as a damaged (or “fallen”) person who will never be free of demons anyway. I trust because it leads to better outcomes, but should the outcomes go awry, I will trust because it is good to trust. And likewise with love, hope, etc. You know: this all “is what it is,” and cannot be controlled. We can only shift how we respond to things.

And, lastly, how have your parents influenced or informed your own way of parenting?

Oh, in so many ways! My parents were, for all their faults, extraordinarily non-judgmental; I struggle to remember them giving me any advice, for example, or seeming to want me to be any particular way other. They didn’t worry terribly much about who we were becoming, my sister and I, didn't try to ensure that we shared their beliefs or tastes or values, and thus they made it easier for us to do so when we naturally aligned. They were supportive, but hands-off. They did not plan activities to fill our time; they lived their lives and involved us as it made sense to, but also left us to our own devices. They both seemed very brave and frank to me, and I’ve tried to be brave and frank myself with our kids: not passing on my worries, not sharing my anxieties, trusting that whatever happens is what we’re here to confront and manage, etc.

They also talked to us as adults from the jump, exposed us to complex and mature works of art, made sure we experienced both “high” and “low” cultures wherever possible, and let us find our ways from a position of familiarity with many possibilities, many “ways of being.” My parents would have loved me whether I’d been a redneck or a professor, a bohemian or a yuppie; they loved me when I was a miserable and angry person and when I was a happy and giving person; it wasn’t “unconditional”—they had the things they found distasteful, they were scornful of self-deception or unethical behavior, and my mother in particular had extreme opinions that I still hear in my mind to this day—but they didn’t co-locate their egos in us. We were our own people, nearly from the jump. And they never, ever, ever guilt-tripped us, about anything. That was a gift.

I also read Kizzy (and soon, Raines) the books they read me, share the music they played for me, take her to the places they took me, as much as possible.

And in opposition: I am sober, I am as even as can be, and I try to be less intense and judgmental than they were. I take the lessons of their lives, as they told them to me, seriously and seek to avoid some of their mistakes.

Is there a question that you wish I would have asked you?

Nothing springs to mind! I feel slightly out of place on this (wonderful) Substack, because when elderly parents commit suicide, much of what makes suicide so painful is missing; theirs were not lives cut short, exactly, and the pain e.g. my wife experiences about her father is quite a distinct and much less manageable pain than anything I’ve gone through. But if this is of use to anyone, I’ll be very glad. They were cool people, they did their best, but as my father liked to say: “Everyone is defeated by life at some point or another.” To me, it doesn’t invalidate anything; it’s just one more irreducible knot to work on, probably forever, while I make my own way toward my end.

Jeez Louise, Mills! Thank you for all that you have shared here. Truly. I’ll be thinking about and revisiting our conversation again and again because you’ve said so many things here that make total sense and carry such profound wisdom. I’m amazed by your resilience, your fortitude, and your optimism, and I feel very honored to publish this significant piece of your life story. I cannot thank you enough for taking the time to so very thoughtfully answer all of my questions, but I’ll try: THANK YOU!!!

If you (or someone you know) is dealing with suicide grief, please consider sharing this post, commenting, or tapping that heart below. Tell us your story, offer any advice or wisdom gained through your own personal experience, and/or let us know which details of

’s story you found relatable, helpful, or insightful.Wherever you are in your journey, know that you deserve peace, hope, and love.

Human/Mother is a publication designed for humans who are also parents and dealing with some pretty heavy life stuff. You can peruse, choose, and take what you need here.

My Brother's Birthday

March 6 of this year was what would have been my little brother’s twenty-third birthday.

My Parental Estrangement Story

My three-year-old daughter selected Llama Llama for me to read during bedtime last week.

Mills, thank you for this, deeply. My own parents are still around but i have cut them out of my life (for their good and mine) which is it’s own, different thing. I labor under the strange “burden of NOT talking about” some of the events of my own life (a turn of phrase i find useful even though i still cant talk about it). But the clarity, perspective, and dare i say “serenity” you project, whether or not you feel it, is infectious. I really wonder what i will feel when my parents eventually die, and i think you’d dislike me saying youve offered a map but youve certainly offered an example of candor with ones circumstances. We need not lie to ourselves, need not overblow events nor under-state them. They “simply” are. And we can draw conclusions from that and change our lives from that but we cant change *them*. Being able to accept them, in life and death, feels like a path to peace.

Thanks, Mills. God bless you and yours! And thanks Katrina for doing this interview. Wonderful work being done here!

This was great! I have similar parents, though perhaps my mother is a bit more unstable while my father has yet to develop an addiction. In terms of talking to kids about it - my grandfather died by suicide, and I was told a watered-down version as a kid. And then never told the truth until I started asking questions in my 40s. To realize everything I was told was a lie — I felt, once again, ignored and minimized. Had I not asked what really happened, I never would have learned the beautiful along with the horror, like he died with a picture of me in his wallet - the only picture. I don’t blame my parents so much for not being honest, as society makes it very hard to talk about suicide, especially to kids.